Eggs as food

A fried egg | |

Humans and their hominid relatives have consumed eggs for millions of years.[1] The most widely consumed eggs are those of fowl, especially chickens. People in Southeast Asia began harvesting chicken eggs for food by 1500 BCE.[2] Eggs of other birds, such as ducks and ostriches, are eaten regularly but much less commonly than those of chickens. People may also eat the eggs of reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Fish eggs consumed as food are known as roe or caviar.

Hens and other egg-laying creatures are raised throughout the world, and mass production of chicken eggs is a global industry. In 2009, an estimated 62.1 million metric tons of eggs were produced worldwide from a total laying flock of approximately 6.4 billion hens.[3] There are issues of regional variation in demand and expectation, as well as current debates concerning methods of mass production. In 2012, the European Union banned battery husbandry of chickens.

History

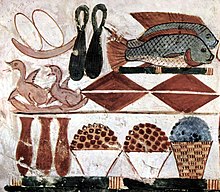

Bird eggs have been valuable foodstuffs since prehistory, in both hunting societies and more recent cultures where birds were domesticated. The chicken was most likely domesticated for its eggs (from jungle fowl native to tropical and subtropical Southeast Asia and Indian subcontinent) before 7500 BCE. Chickens were brought to Sumer and Egypt by 1500 BCE, and arrived in Greece around 800 BCE, where the quail had been the primary source of eggs.[4] In Thebes, Egypt, the tomb of Haremhab, dating to approximately 1420 BCE, shows a depiction of a man carrying bowls of ostrich eggs and other large eggs, presumably those of the pelican, as offerings.[5] In ancient Rome, eggs were preserved using a number of methods and meals often started with an egg course.[5] The Romans crushed the shells in their plates to prevent evil spirits from hiding there.[6]

In the Middle Ages, eggs were forbidden during Lent because of their richness,[6] although the motivation for forgoing eggs during Lent was not entirely religious. An annual pause in egg consumption allowed farmers to rest their flocks, and also to limit their hens' consumption of feed during a time of year when food stocks were usually scarce.

Eggs scrambled with acidic fruit juices were popular in France in the seventeenth century; this may have been the origin of lemon curd.[7]

The dried egg industry developed in the nineteenth century, before the rise of the frozen egg industry.[8] In 1878, a company in St. Louis, Missouri started to transform egg yolk and egg white into a light-brown, meal-like substance by using a drying process.[8] The production of dried eggs significantly expanded during World War II, for use by the United States Armed Forces and its allies.[8]

In 1911, the egg carton was invented by Joseph Coyle in Smithers, British Columbia, to solve a dispute about broken eggs between a farmer in Bulkley Valley and the owner of the Aldermere Hotel. Early egg cartons were made of paper.[9] Polystyrene egg cartons became popular in the latter half of the twentieth century as they were perceived to offer better protection especially against heat and breakage, however, by the twenty-first century environmental considerations have led to the return of more biodegradable paper cartons (often made of recycled material) that once again became more widely used.

Whereas the wild Asian fowl from which domesticated chickens are descended typically lay about a dozen eggs each year during the breeding season, several millennia of selective breeding have produced domesticated hens capable of laying more than three hundred eggs each annually, and to lay eggs year round.

Varieties

Bird eggs are a common food and one of the most versatile ingredients used in cooking. They are important in many branches of the modern food industry.[6]

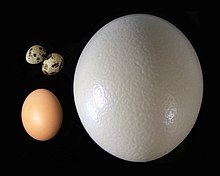

The most commonly used bird eggs are those from the chicken, duck, and goose. Smaller eggs, such as quail eggs, are used occasionally as a gourmet ingredient in Western countries. Eggs are a common everyday food in many parts of Asia, such as China and Thailand, with Asian production providing 59 percent of the world total in 2013.[10]

The largest bird eggs, from ostriches, tend to be used only as special luxury food. Gull eggs are considered a delicacy in England,[11] as well as in some Scandinavian countries, particularly in Norway. In some African countries, guineafowl eggs often are seen in marketplaces, especially in the spring of each year.[12] Pheasant eggs and emu eggs are edible, but less widely available;[11] sometimes they are obtainable from farmers, poulterers, or luxury grocery stores. In many countries, wild bird eggs are protected by laws which prohibit the collecting or selling of them, or permit collection only during specific periods of the year.[11]

Production

In 2017, world production of chicken eggs was 80.1 million tonnes. The largest producers were China with 31.3 million of this total, the United States with 6.3 million, India at 4.8 million, Mexico at 2.8 million, Japan at 2.6 million, and Brazil and Russia with 2.5 million each.[13] The largest egg factory in British Columbia, for example, ships 12 million eggs per week.[14]

For the month of January 2019, the United States produced 9.41 billion eggs, with 8.2 billion for table consumption and 1.2 billion for raising chicks.[15] Americans are projected to each consume 279 eggs in 2019, the highest since 1973, but less than the 405 eggs eaten per person in 1945.[15]

During production, eggs can be candled to check their quality.[16] The size of an egg's air cell is determined, and if fertilization took place three to six days or earlier prior to the candling, blood vessels can typically be seen as evidence that the egg contains an embryo.[16] Contrary to common misconception, this is not conclusive evidence of fertilization, as blood vessels can just denote an ordinary rupture on the egg yolk surface while the egg was forming.[17] Depending on local regulations, eggs may be washed before being placed in egg boxes, although washing may shorten their length of freshness.

Anatomy and characteristics

- Eggshell

- Outer membrane

- Inner membrane

- Chalaza

- Exterior albumen

- Middle albumen

- Vitelline membrane

- Nucleus of Pander

- Germinal disc (nucleus)

- Yellow yolk

- White yolk

- Internal albumen

- Chalaza

- Air cell

- Cuticula

Bird and reptile eggs consist of a protective eggshell, albumen (egg white), and vitellus (egg yolk), contained within various thin membranes. The egg yolk is suspended in the egg white by one or two spiral bands of tissue called the chalazae (from the Greek word χάλαζα, meaning 'hailstone' or 'hard lump'). The shape of a chicken egg resembles a prolate spheroid with one end larger than the other and has cylindrical symmetry along the long axis.

Air cell

The larger end of the egg contains an air cell that forms when the contents of the egg cool down and contract after it is laid. Chicken eggs are graded according to the size of this air cell, measured during candling. A very fresh egg has a small air cell and receives a grade of AA. As the size of the air cell increases and the quality of the egg decreases, the grade moves from AA to A to B. This provides a way of testing the age of an egg: as the air cell increases in size due to air being drawn through pores in the shell as water is lost, the egg becomes less dense and the larger end of the egg will rise to increasingly shallower depths when the egg is placed in a bowl of water. A very old egg will float in the water and should not be eaten,[18] especially if a foul odor can be detected if the egg is cracked open.[19]

Shell

Eggshell color is caused by pigment deposition during egg formation in the oviduct and may vary according to species and breed, from the more common white or brown to pink or speckled blue-green. The brown pigment is protoporphyrin IX, a precursor of heme, and the blue pigment is biliverdin, a product of the breakdown of heme.[20][21] Generally, chicken breeds with white ear lobes lay white eggs, whereas chickens with red ear lobes lay brown eggs.[22] Although there is no significant link between shell color and nutritional value, often there is a cultural preference for one color over another (see § Color of eggshell below). As candling is less effective with brown eggs, they have a significantly higher incidence of blood spots.[23]

Membrane

The eggshell membrane is a clear film lining the eggshell, visible when one peels a boiled egg. Primarily, it is composed of fibrous proteins such as collagen type I.[24] These membranes may be used commercially as a dietary supplement.

White

"White" is the common name for the clear liquid (also called the albumen or the glair/glaire) contained within an egg. Colorless and transparent initially, upon cooking it turns white and opaque. In chickens, it is formed from the layers of secretions of the anterior section of the hen oviduct during the passage of the egg.[25] It forms around both fertilized and unfertilized yolks. The primary natural purpose of egg white is to protect the yolk and provide additional nutrition during the growth of the embryo.

Egg white consists primarily of approximately 90 percent water into which is dissolved 10 percent proteins (including albumins, mucoproteins, and globulins). Unlike the yolk, which is high in lipids (fats), egg white contains almost no fat and the carbohydrate content is less than one percent. Egg white has many uses in food and many other applications, including the preparation of vaccines, such as those for influenza.[26]

Yolk

The yolk in a newly laid egg is round and firm. As the yolk ages, it absorbs water from the albumen, which increases its size and causes it to stretch and weaken the vitelline membrane (the clear casing enclosing the yolk). The resulting effect is a flattened and enlarged yolk shape.

Yolk color is dependent on the diet of the hen. If the diet contains yellow or orange plant pigments known as xanthophylls, then they are deposited in the yolk, coloring it. Lutein is the most abundant pigment in egg yolk.[27] A diet without such colorful foods may result in an almost colorless yolk. Yolk color is, for example, enhanced if the diet includes foods such as yellow corn and marigold petals.[28] In the US, the use of artificial color additives is forbidden.[28]

Abnormalities

Abnormalities that have been found in eggs purchased for human consumption include:

- Double-yolk eggs, when an egg contains two or more yolks, occurs when ovulation occurs too rapidly, or when one yolk becomes joined with another yolk.[29]

- Yolkless eggs, which contain whites but no yolk, usually occurs during a pullet's first effort, produced before her laying mechanism is fully ready.[30]

- Double-shelled eggs, where an egg may have two or more outer shells, is caused by a counter-peristalsis contraction and occurs when a second oocyte is released by the ovary before the first egg has completely traveled through the oviduct and been laid.[31]

- Shell-less or thin-shelled eggs may be caused by egg drop syndrome.[32]

Culinary properties

Types of dishes

Chicken eggs are widely used in many types of dishes, both sweet and savory, including many baked goods. Some of the most common preparation methods include scrambled, fried, poached, hard-boiled, soft-boiled, omelettes, and pickled. They also may be eaten raw, although this is not recommended for people who may be especially susceptible to salmonellosis, such as the elderly, the infirm, or pregnant women. In addition, the protein in raw eggs is only 51 percent bioavailable, whereas that of a cooked egg is nearer 91 percent bioavailable, meaning the protein of cooked eggs is nearly twice as absorbable as the protein from raw eggs.[33]

As a cooking ingredient, egg yolks are an important emulsifier in the kitchen, and are also used as a thickener, as in custards.

The albumen (egg white) contains protein, but little or no fat, and may be used in cooking separately from the yolk. The proteins in egg white allow it to form foams and aerated dishes. Egg whites may be aerated or whipped to a light, fluffy consistency, and often are used in desserts such as meringues and mousse.

Ground eggshells sometimes are used as a food additive to deliver calcium.[34] Every part of an egg is edible, although the eggshell is generally discarded. Some recipes call for immature or unlaid eggs, which are harvested after the hen is slaughtered or cooked, while still inside the chicken.[35]

Cooking

Eggs contain multiple proteins that gel at different temperatures within the yolk and the white, and the temperature determines the gelling time. Egg yolk becomes a gel, or solidifies, between 61 and 70 °C (142 and 158 °F). Egg white gels at different temperatures: 60 to 73 °C (140 to 163 °F). The white contains exterior albumen which sets at the highest temperature. In practice, in many cooking processes the white gels first because it is exposed to higher temperatures for longer.[36]

Salmonella is killed instantly at 71 °C (160 °F), but also is killed from 54.5 °C (130.1 °F), if held at that temperature for sufficiently long time periods. To avoid the issue of salmonella, eggs may be pasteurized in-shell at 57 °C (135 °F) for an hour and 15 minutes. Although the white then is slightly milkier, the eggs may be used in normal ways. Whipping for meringue takes significantly longer, but the final volume is virtually the same.[37]

If a boiled egg is overcooked, a greenish ring sometimes appears around the egg yolk due to changes to the iron and sulfur compounds in the egg.[38] It also may occur with an abundance of iron in the cooking water.[39] Overcooking harms the quality of the protein.[40] Chilling an overcooked egg for a few minutes in cold water until it is completely cooled may prevent the greenish ring from forming on the surface of the yolk.[41]

Peeling a cooked egg is easiest when the egg was put into boiling water as opposed to slowly heating the egg from a start in cold water.[42]

Flavor variations

Although the age of the egg and the conditions of its storage have a greater influence, the bird's diet affects the flavor of the egg.[7] For example, when a brown-egg chicken breed eats rapeseed (canola) or soy meals, its intestinal microbes metabolize them into fishy-smelling triethylamine, which ends up in the egg.[7] The unpredictable diet of free-range hens will produce likewise, unpredictable egg flavors.[7] Duck eggs tend to have a flavor distinct from, but still resembling, chicken eggs.

Eggs may be soaked in mixtures to absorb flavor. Tea eggs, a common snack sold from street-side carts in China, are steeped in a brew from a mixture of various spices, soy sauce, and black tea leaves to give flavor. Hard boiled eggs are cracked slightly before being simmered in the marinade for more flavor, also giving them their marble pattern.[43]

Storage

Careful storage of edible eggs is extremely important, as an improperly handled egg may contain elevated levels of Salmonella bacteria that may cause severe food poisoning. In the US, eggs are washed. This cleans the shell, but erodes its cuticle.[44][45] The USDA thus recommends refrigerating eggs to prevent the growth of Salmonella.[28]

Refrigeration also preserves the taste and texture.[46][unreliable source?] In Europe, eggs are not usually washed, and the shells are dirtier, however the cuticle is undamaged, and they do not require refrigeration.[45][unreliable source?] In the UK in particular, hens are immunized against salmonella and generally, their eggs are safe for 21 days.[45]

Preservation

The simplest method to preserve an egg is to treat it with salt. Salt draws water out of bacteria and molds, which prevents their growth.[47] The Chinese salted duck egg is made by immersing duck eggs in brine, or coating them individually with a paste of salt and mud or clay. The eggs stop absorbing salt after approximately a month, having reached osmotic equilibrium.[47] Their yolks take on an orange-red color and solidify, but the white remains somewhat liquid. These often are boiled before consumption and are served with rice congee.

Another method is to make pickled eggs, by boiling them first and immersing them in a mixture of vinegar, salt, and spices, such as ginger or allspice. Frequently, beetroot juice is added to impart a red color to the eggs.[48] If the eggs are immersed in it for a few hours, the distinct red, white, and yellow colors may be seen when the eggs are sliced.[48] If marinated for several days or more, the red color will reach the yolk.[48] If the eggs are marinated in the mixture for several weeks or more, the vinegar will dissolve much of the shell's calcium carbonate and penetrate the egg, making it acidic enough to inhibit the growth of bacteria and molds.[47] Pickled eggs made this way generally keep for a year or more without refrigeration.[47]

A century egg or hundred-year-old egg is preserved by coating an egg in a mixture of clay, wood ash, salt, lime, and rice straw for several weeks to several months, depending on the method of processing. After the process is completed, the yolk becomes a dark green, cream-like substance with a strong odor of sulfur and ammonia, while the white becomes a dark brown, transparent jelly with a comparatively mild, distinct flavor. The transforming agent in a century egg is its alkaline material, which gradually raises the pH of the egg from approximately 9 to 12 or more.[49] This chemical process breaks down some of the complex, flavorless proteins and fats of the yolk into simpler, flavorful ones, which in some way may be thought of as an "inorganic" version of fermentation.

Nutrition and health effects

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 647 kJ (155 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1.12 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

10.6 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

12.6 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tryptophan | 0.153 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Threonine | 0.604 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isoleucine | 0.686 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leucine | 1.075 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lysine | 0.904 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Methionine | 0.392 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cystine | 0.292 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phenylalanine | 0.668 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tyrosine | 0.513 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Valine | 0.767 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arginine | 0.755 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Histidine | 0.298 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alanine | 0.700 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aspartic acid | 1.264 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Glutamic acid | 1.644 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Glycine | 0.423 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proline | 0.501 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Serine | 0.936 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 75 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cholesterol | 373 mg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

For edible portion only. Refuse: 12% (shell). An egg just large enough to be classified as "large" in the U.S. yields 50 grams of egg without shell. This size egg is classified as "medium" in Europe and "standard" in New Zealand. Link to USDA Database entry | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[50] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[51] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Egg yolks and whole eggs store significant amounts of protein and choline.[52][53] Due to their protein content, the United States Department of Agriculture formerly categorized eggs as Meat within the Food Guide Pyramid (now MyPlate).[52]

A 50-gram (1.8 oz) medium/large chicken egg provides approximately 70 kilocalories (290 kJ) of food energy and 6 grams of protein.[54][55]

Eggs (boiled) supply several vitamins and minerals as significant amounts of the Daily Value (DV), including (per 100g) vitamin A (19% DV), riboflavin (42% DV), pantothenic acid (28% DV), vitamin B12 (46% DV), choline (60% DV), phosphorus (25% DV), zinc (11% DV) and vitamin D (15% DV). Cooking methods affect the nutritional values of eggs.[clarify]

The diet of laying hens also may affect the nutritional quality of eggs. For instance, chicken eggs that are especially high in omega-3 fatty acids are produced by feeding hens a diet containing polyunsaturated fats from sources such as fish oil, chia seeds, or flaxseeds.[56] Pasture-raised free-range hens, which forage for their own food, also produce eggs that are relatively enriched in omega-3 fatty acids when compared to those of cage-raised chickens.[57][58]

A 2010 USDA study determined there were no significant differences of macronutrients in various chicken eggs.[59]

Cooked eggs are easier to digest than raw eggs,[60] as well as having a lower risk of salmonellosis.[61]

Cholesterol and fat

More than half the calories found in eggs come from the fat in the yolk; 50 grams of chicken egg (the contents of an egg just large enough to be classified as "large" in the US, but "medium" in Europe) contains approximately five grams of fat. Saturated fat (palmitic, stearic, and myristic acids) makes up 27 percent of the fat in an egg.[62] The egg white consists primarily of water (88 percent) and protein (11 percent), with no cholesterol and 0.2 percent fat.[63]

There is debate over whether egg yolk presents a health risk. Some research suggests dietary cholesterol increases the ratio of total to HDL cholesterol and, therefore, adversely affects the body's cholesterol profile;[64] whereas other studies show that moderate consumption of eggs, up to one a day, does not appear to increase heart disease risk in healthy individuals.[65] Harold McGee argues that the cholesterol in the egg yolk is not what causes a problem, because fat (particularly saturated fat) is much more likely to raise cholesterol levels than the consumption of cholesterol.[18]

Type 2 diabetes

Studies have shown conflicting results about a possible connection between egg consumption and type 2 diabetes.

A meta-analysis from 2013 found that eating four eggs per week was associated with a 29 percent increase in the relative risk of developing diabetes.[66] Another meta-analysis from 2013 also supported the idea that egg consumption may lead to an increased incidence of type two diabetes.[67] A 2016 meta-analysis suggested that association of egg consumption with increased risk of incident type 2 diabetes may be restricted to cohort studies from the United States.[68]

A 2020 meta-analysis found that there was no overall association between moderate egg consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes and that the risk found in US studies was not found in European or Asian studies.[69]

Cancer

A 2015 meta-analysis found an association between higher egg consumption (five a week) with increased risk of breast cancer compared to no egg consumption.[70] Another meta-analysis found that egg consumption may increase ovarian cancer risk.[71]

A 2019 meta-analysis found an association between high egg consumption and risk of upper aero-digestive tract cancers in hospital-based case-control studies.[72]

A 2021 review did not find a significant association between egg consumption and breast cancer.[73] A 2021 umbrella review found that egg consumption significantly increases the risk of ovarian cancer.[74]

Cardiovascular health

One systematic review and meta-analysis of egg consumption found that higher consumption of eggs (more than 1 egg/day) was associated with a significant reduction in risk of coronary artery disease.[75] Another systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary cholesterol and egg consumption found that egg consumption was associated with an increased all-cause mortality and CVD mortality.[76] These contrary results may be due to somewhat different methods of study selection and the use primarily of observational studies, where confounding factors are not controlled.[77]

A 2018 meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials found that consumption of eggs increases total cholesterol (TC), LDL-C and HDL-C compared to no egg-consumption but not to low-egg control diets.[78] In 2020, two meta-analyses found that moderate egg consumption (up to one egg a day) is not associated with an increased cardiovascular disease risk.[79][80] A 2020 umbrella review concluded that increased egg consumption is not associated with cardiovascular disease risk in the general population.[81] Another umbrella review found no association between egg consumption and cardiovascular disorders.[82]

A 2013 meta-analysis found no association between egg consumption and heart disease or stroke.[83][84] A 2013 systematic review and meta-analysis found no association between egg consumption and cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular disease mortality, but did find egg consumption of more than once daily increased cardiovascular disease risk 1.69-fold in those with type 2 diabetes mellitus when compared to type 2 diabetics who ate less than one egg per week.[67] Another 2013 meta-analysis found that eating four eggs per week increased the risk of cardiovascular disease by six percent.[66]

Eggs are one of the largest sources of phosphatidylcholine (lecithin) in the human diet.[85] A study published in the scientific journal, Nature, showed that dietary phosphatidylcholine is digested by bacteria in the gut and eventually converted into the compound TMAO, a compound linked with increased heart disease.[86][87] Another study found that type 2 diabetes mellitus and kidney disease also increase TMAO levels and that evidence for a link between TMAO and cardiovascular diseases may be due to confounding or reverse causality.[88]

Other

Egg consumption does not increase hypertension risk.[89][90] A 2016 meta-analysis found that consumption of up to one egg a day may contribute to a decreased risk of total stroke.[91] Two recent meta-analyses found no association between egg intake and risk of stroke.[92][93]

A 2019 meta-analysis revealed that egg consumption has no significant effect on serum biomarkers of inflammation.[94] A 2021 review of clinical trials found that egg consumption has beneficial effects on macular pigment optical density and serum lutein.[95]

Contamination

A health issue associated with eggs is contamination by pathogenic bacteria, such as Salmonella enteritidis. Contamination of eggs with other members of the genus Salmonella while exiting a female bird via the cloaca may occur, so care must be taken to prevent the egg shell from becoming contaminated with fecal matter. In commercial practice in the US, eggs are quickly washed with a sanitizing solution within minutes of being laid. The risk of infection from raw or undercooked eggs is dependent in part upon the sanitary conditions under which the hens are kept.

Health experts advise people to refrigerate washed eggs, use them within two weeks, cook them thoroughly, and never consume raw eggs.[61] As with meat, containers and surfaces that have been used to process raw eggs should not come in contact with ready-to-eat food.

A study by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 2002 (Risk Analysis April 2002 22(2):203-18) suggests the problem is not so prevalent in the U.S. as once thought. It showed that of the 69 billion eggs produced annually, only 2.3 million are contaminated with Salmonella—equivalent to just one in every 30,000 eggs—thus showing Salmonella infection is quite rarely induced by eggs. This has not been the case in other countries, however, where Salmonella enteritidis and Salmonella typhimurium infections due to egg consumption are major concerns.[96][97][98] Egg shells act as hermetic seals that guard against bacteria entering, but this seal can be broken through improper handling or if laid by unhealthy chickens. Most forms of contamination enter through such weaknesses in the shell. In the UK, the British Egg Industry Council awards the lions stamp to eggs that, among other things, come from hens that have been vaccinated against Salmonella.[99][100][101]

In 2017, authorities blocked millions of eggs from sale in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany because of contamination with the insecticide fipronil.[102]

Food allergy

One of the most common food allergies in infants is eggs.[103] Infants usually have the opportunity to grow out of this allergy during childhood, if exposure is minimized.[104] Allergic reactions against egg white are more common than reactions against egg yolks.[105] In addition to true allergic reactions, some people experience a food intolerance to egg whites.[105] Food labeling practices in most developed countries now include eggs, egg products, and the processing of foods on equipment that also process foods containing eggs in a special allergen alert section of the ingredients on the labels.[106]

Farming

Most commercially farmed chicken eggs intended for human consumption are unfertilized, since the laying hens are kept without roosters. Fertile eggs may be eaten, with little nutritional difference when compared to the unfertilized. Fertile eggs will not contain a developed embryo, as refrigeration temperatures inhibit cellular growth for an extended period of time. Sometimes an embryo is allowed to develop, but eaten before hatching as with balut.

Grading by quality and size

The U.S. Department of Agriculture grades eggs by the interior quality of the egg (see Haugh unit) and the appearance and condition of the egg shell. Eggs of any quality grade may differ in weight (size).

- U.S. Grade AA

- Eggs have whites that are thick and firm; have yolks that are high, round, and practically free from defects; and have clean, unbroken shells.

- Grade AA and Grade A eggs are best for frying and poaching, where appearance is important.

- U.S. Grade A

- Eggs have characteristics of Grade AA eggs except the whites are "reasonably" firm.

- This is the quality most often sold in stores.

- U.S. Grade B

- Eggs have whites that may be thinner and yolks that may be wider and flatter than eggs of higher grades. The shells must be unbroken, but may show slight stains.

- This quality is seldom found in retail stores because usually they are used to make liquid, frozen, and dried egg products, as well as other egg-containing products.

In Australia[107] and the European Union, eggs are graded by the hen raising method, free range, battery caged, etc.

Chicken eggs are graded by size for the purpose of sales. Some maxi eggs may have double-yolks and some farms separate out double-yolk eggs for special sale.[108]

-

Comparison of an egg and a maxi egg with a double-yolk - closed (1/2)

-

Comparison of an egg and a maxi egg with a double-yolk - opened (2/2)

-

Double-yolk egg - opened

Color of eggshell

Although eggshell color is a largely cosmetic issue, with no effect on egg quality or taste, it is a major issue in production due to regional and national preferences for specific colors, and the results of such preferences on demand. For example, in most regions of the United States, chicken eggs generally are white. However, brown eggs are more common in some parts of the Northeastern United States, particularly New England, where a television jingle for years proclaimed "brown eggs are local eggs, and local eggs are fresh!".[109] Local chicken breeds, including the Rhode Island Red, lay brown eggs. Brown eggs are preferred in China, Costa Rica, Ireland, France, and the United Kingdom. In Brazil and Poland, white chicken eggs are generally regarded as industrial, and brown or reddish ones are preferred. Small farms and smallholdings, particularly in economically advanced nations, may sell eggs of widely varying colors and sizes, with combinations of white, brown, speckled (red), green, and blue (as laid by certain breeds, including araucanas,[110] heritage skyline, and cream leg bar) eggs in the same box or carton, while the supermarkets at the same time sell mostly eggs from the larger producers, of the color preferred in that nation or region.

These cultural trends have been observed for many years. The New York Times reported during the Second World War that housewives in Boston preferred brown eggs and those in New York preferred white eggs.[111] In February 1976, the New Scientist magazine, in discussing issues of chicken egg color, stated "Housewives are particularly fussy about the colour of their eggs, preferring even to pay more for brown eggs although white eggs are just as good".[112] As a result of these trends, brown eggs are usually more expensive to purchase in regions where white eggs are considered "normal", due to lower production.[113] In France and the United Kingdom, it is very difficult to buy white eggs, with most supermarkets supplying only the more popular brown eggs. By direct contrast, in Egypt it is very hard to source brown eggs, as demand is almost entirely for white ones, with the country's largest supplier describing white eggs as "table eggs" and packaging brown eggs for export.[114]

Research conducted by a French institute in the 1970s demonstrated blue chicken eggs from the Chilean araucana fowl may be stronger and more resilient to breakage.[112]

Research at Nihon University, Japan in 1990 revealed a number of different issues were important to Japanese housewives when deciding which eggs to buy and that color was a distinct factor, with most Japanese housewives preferring the white color.[115]

Egg producers carefully consider cultural issues, as well as commercial ones, when selecting the breed or breeds of chickens used for production, as egg color varies between breeds.[116] Among producers and breeders, brown eggs often are referred to as "tinted", while the speckled eggs preferred by some consumers often are referred to as being "red" in color.[117]

Living conditions of birds

Commercial factory farming operations often involve raising the hens in small, crowded cages, preventing the chickens from engaging in natural behaviors, such as wing-flapping, dust-bathing, scratching, pecking, perching, and nest-building. Such restrictions may lead to pacing and escape behavior.[118]

Many hens confined to battery cages, and some raised in cage-free conditions, are debeaked to prevent them from harming each other and engaging in cannibalism. According to critics of the practice, this can cause hens severe pain to the point where some may refuse to eat and starve to death. Some hens may be forced to molt to increase egg quality and production level after the molting.[119] Molting can be induced by extended food withdrawal, water withdrawal, or controlled lighting programs.

Laying hens often are euthanized when reaching 100 to 130 weeks of age, when their egg productivity starts to decline.[120] Due to modern selective breeding, laying hen strains differ from meat production strains. As male birds of the laying strain do not lay eggs and are not suitable for meat production, they generally are killed soon after they hatch.[121]

Free-range eggs are considered by some advocates to be an acceptable substitute to factory-farmed eggs. Free-range laying hens are given outdoor access instead of being contained in crowded cages. Questions regarding the living conditions of free-range hens have been raised in the United States of America, as there is no legal definition or regulations for eggs labeled as free-range in that country.[122]

In the United States, increased public concern for animal welfare has pushed various egg producers to promote eggs under a variety of standards. The most widespread standard in use is determined by United Egg Producers through their voluntary program of certification.[123] The United Egg Producers program includes guidelines regarding housing, food, water, air, living space, beak trimming, molting, handling, and transportation, however, opponents such as The Humane Society have alleged UEP certification is misleading and allows a significant amount of unchecked animal cruelty.[124] Other standards include "Cage Free", "Natural", "Certified Humane", and "Certified Organic". Of these standards, "Certified Humane", which carries requirements for stocking density and cage-free keeping and so on, and "Certified Organic", which requires hens to have outdoor access and to be fed only organic vegetarian feed and so on, are the most stringent.[125][126]

Effective 1 January 2012, the European Union banned conventional battery cages for egg-laying hens, as outlined in EU Directive 1999/74/EC.[127] The EU permits the use of "enriched" furnished cages that must meet certain space and amenity requirements. Egg producers in many member states have objected to the new quality standards while in some countries, even furnished cages and family cages are subject to be banned as well. The production standard of the eggs is visible on a mandatory egg marking categorization where the EU egg code begins with 3 for caged chicken to 1 for free-range eggs and 0 for organic egg production.

Killing of male chicks

In all methods of egg production, unwanted male chicks are killed at birth during the process of securing a further generation of egg-laying hens.[128] As of June 2023, this practice has been banned in Germany, France, and Italy.[129] Some egg producers have adopted in-ovo sexing, which first became available in 2018.[130] As of September 2023, five companies have commercially available in-ovo sexing technology, which is used for 15 percent of the European layer population.[131]

Cultural significance

A popular Easter tradition in some parts of the world is a decoration of hard-boiled eggs (usually by dyeing, but often by spray-painting). A similar tradition of egg painting exists in areas of the world influenced by the culture of Persia. Before the spring equinox in the Persian New Year tradition (called Norouz), each family member decorates a hard-boiled egg and they set them together in a bowl.[132]

In the New Testament, eggs are referred to as an example of the kind of gift a child might request from their father, and which would not be denied.[133]

In Northern Europe and North America, Easter eggs may be hidden by adults for children to find in an Easter egg hunt. They may be rolled in some traditions.[134]

In Eastern and Central Europe, and parts of England, easter eggs may be tapped against each other to see whose egg breaks first.[135]

Since the sixteenth century, the tradition of a dancing egg is held during the feast of Corpus Christi in Barcelona and other Catalan cities. It consists of a hollow eggshell, positioned over the water jet from a fountain, which causes the eggshell to revolve without falling.[136]

Fraud

In China, egg food fraud in the form of fake chicken eggs made from resin, starch and pigments, for both domestic consumption and exports are a growing concern.[137][138][139][140][141]

See also

References

- ^ Kenneth F. Kiple, A Movable Feast: Ten Millennia of Food Globalization (2007), p. 22.

- ^ Peters, Joris; Lebrasseur, Ophélie; Irving-Pease, Evan K.; et al. (14 June 2022). "The biocultural origins and dispersal of domestic chickens". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (24): e2121978119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11921978P. doi:10.1073/pnas.2121978119. PMC 9214543. PMID 35666876.

- ^ Outlook for egg production Archived 15 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine WATT Ag Net – Watt Publishing Co

- ^ McGee, Harold (2004). McGee on Food and Cooking. Hodder and Stoughton. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-340-83149-6.

- ^ a b Brothwell, Don R.; Patricia Brothwell (1997). Food in Antiquity: A Survey of the Diet of Early Peoples. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-0-8018-5740-9.

- ^ a b c Montagne, Prosper (2001). Larousse Gastronomique. Clarkson Potter. pp. 447–448. ISBN 978-0-609-60971-2.

- ^ a b c d McGee, Harold (2004). On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. Scribner. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-684-80001-1.

- ^ a b c Stadelman, William (1995). Egg Science and Technology. Haworth Press. pp. 221–223. ISBN 978-1-56022-854-7.

- ^ Easterday, Jim (21 April 2005). "The Coyle Egg-Safety Carton". Hiway16 Magazine. Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 21 April 2008.

- ^ "Global Poultry Trends 2014: Rapid Growth in Asia's Egg Output". The Poultry Site. 6 May 2015. Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ a b c Roux, Michel; Martin Brigdale (2006). Eggs. Wiley. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-471-76913-2.

- ^ Stadelman, William (1995). Egg Science and Technology. Haworth Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-56022-854-7.

- ^ "Eggs, hen, in shell; Production/Livestock Primary for World in 2017". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Statistics Division (FAOSTAT). 2019. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ Quito, Anne (11 May 2017). "Target used 16,000 eggs to decorate a dinner party, in a grand display of design's wastefulness". Quartz (publication). Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ a b Varley, Kevin; Carey, Dominic (27 February 2019). "The U.S. produced enough eggs in January to reach the Moon". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Candling eggs". University of Illinois Extension. 2019. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

Eggs are candled to determine the condition of the air cell, yolk, and white. Candling detects bloody whites, blood spots, or meat spots, and enables observation of germ development. Candling is done in a darkened room with the egg held before a light. The light penetrates the egg and makes it possible to observe the inside of the egg. Incubated eggs are candled to determine whether they are fertile and, if fertile, to check the growth and development of the embryo

- ^ Wolke, Robert L (16 April 2002). "Egged On". The Washington Post. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ a b McGee, H. (2004). On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. New York: Scribners. ISBN 978-0-684-80001-1.

- ^ "AskUSDA". ask.usda.gov. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ Sachar, M.; Anderson, K. E.; Ma, X. (2016). "Protoporphyrin IX: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 356 (2): 267–275. doi:10.1124/jpet.115.228130. PMC 4727154. PMID 26588930.

- ^ Halepas, Steven; Hamchand, Randy; Lindeyer, Samuel E. D.; Brückner, Christian (2017). "Isolation of Biliverdin IXα, as its Dimethyl Ester, from Emu Eggshells". Journal of Chemical Education. 94 (10): 1533–1537. Bibcode:2017JChEd..94.1533H. doi:10.1021/acs.jchemed.7b00449.

- ^ "Information on chicken breeds" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ Shanker, Deena (19 June 2015). "Here's why your brown eggs have more blood spots than white ones". Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Wong, M.; Hendrix, M.J.; van der Mark, K.; Little, C.; Stern, R. (July 1984). "Collagen in the egg shell membranes of the hen". Dev Biol. 104 (1): 28–36. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(84)90033-2. PMID 6203793.

- ^ Ornithology, Volume 1994 By Frank B. Gill p. 361

- ^ "How Influenza (Flu) Vaccines Are Made". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, US Department of Health and Human Services. 7 November 2016. Archived from the original on 21 November 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ F. Karadas et al., Effects of carotenoids from lucerne, marigold and tomato on egg yolk pigmentation and carotenoid composition. Br Poult Sci. 2006 Oct;47(5):561-6. Karadas, F.; Grammenidis, E.; Surai, P. F.; Acamovic, T.; Sparks, N. H. C. (2006). "Effects of carotenoids from lucerne, marigold and tomato on egg yolk pigmentation and carotenoid composition". British Poultry Science. 47 (5): 561–566. doi:10.1080/00071660600962976. PMID 17050099. S2CID 20868953.

- ^ a b c Shell eggs from farm to table. USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service, (2019).

- ^ Kruszelnicki, Karl S. (2003). "Double-yolked eggs and chicken development". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 14 July 2008. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ Rookledge, K. A; Heald, P. J (25 June 1996). "Dwarf Eggs and the Timing of Ovulation in the Domestic Fowl". Nature. 210 (5043): 1371. doi:10.1038/2101371a0. S2CID 4280287.

- ^ Blaine, E. M; Munroe, S. S (1 January 1969). "The Case of the Double-Shelled Egg". Poultry Science. 48 (1): 349–350. doi:10.3382/ps.0480349. PMID 5389851. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ Spickler, Rovid A (2017). "Egg Drop Syndrome 1976" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ Evenepoel, P.; Geypens, B.; Luypaerts, A.; et al. (1998). "Digestibility of Cooked and Raw Egg Protein in Humans as Assessed by Stable Isotope Techniques". The Journal of Nutrition. 128 (10): 1716–1722. doi:10.1093/jn/128.10.1716. PMID 9772141. Archived from the original on 18 June 2011. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ^ Anne Schaafsma; Gerard M Beelen (1999). "Eggshell powder, a comparable or better source of calcium than purified calcium carbonate: piglet studies". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 79 (12): 1596–1600. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(199909)79:12<1596::AID-JSFA406>3.0.CO;2-A. Archived from the original on 16 December 2012.

- ^ Marian Burros, "What the Egg Was First" Archived 24 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, 7 February 2007

- ^ Vega, César; Mercadé-Prieto, Ruben (2011). "Culinary Biophysics: On the Nature of the 6X°C Egg". Food Biophysics. 6 (1): 152–9. doi:10.1007/s11483-010-9200-1. S2CID 97933856.

- ^ Schuman JD, Sheldon BW, Vandepopuliere JM, Ball HR (October 1997). "Immersion heat treatments for inactivation of Salmonella enteritidis with intact eggs". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 83 (4): 438–44. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.1997.00253.x. PMID 9351225. S2CID 22582907.

- ^ Tinkler, Charles Kenneth; Soar, Marion Crossland (1 April 1920). "The Formation of Ferrous Sulphide in Eggs during Cooking". Biochemical Journal. 14 (2): 114–119. doi:10.1042/bj0140114. ISSN 0006-2936. PMC 1258902. PMID 16742889.

- ^ "What causes a green ring around the yolk of a hard-cooked egg?". AskUSDA. 22 March 2023. Archived from the original on 27 October 2023.

- ^ "overcooked eggs". Times of india. 12 July 2019. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ "How To Make Perfect Hard-Boiled Eggs With No Green Ring". Annapolis, MD Patch. 28 March 2018. Archived from the original on 8 January 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ^ This was shown experimentally and documented in the book The Food Lab: Better Home Cooking Through Science by J. Kenji López-Alt; published 21 September 2015 by W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 978-0-393-08108-4

- ^ Zhu, Maggie (1 June 2018). "Chinese Tea Eggs (w/ Soft and Hard Boiled Eggs, 茶叶蛋)". Omnivore's Cookbook. Retrieved 7 October 2024.

- ^ "Anatomy of an Egg". Science of Cooking. Exploratorium. Archived from the original on 14 November 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ^ a b c Arumugam, Nadia (25 October 2012). "Why American Eggs Would Be Illegal In A British Supermarket, And Vice Versa". Forbes. Archived from the original on 24 October 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ^ How to Store Fresh Eggs Archived 27 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine Mother Earth News, November/December (1977)

- ^ a b c d McGee, Harold (2004). On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. Scribner. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-684-80001-1.

- ^ a b c Stadelman, William (1995). Egg Science and Technology. Haworth Press. pp. 479–480. ISBN 978-1-56022-854-7.

- ^ McGee, Harold (2004). On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. Scribner. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-684-80001-1.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 27 March 2024. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on 9 May 2024. Retrieved 21 June 2024.[page needed]

- ^ a b Agricultural Marketing Service (1995). "How to Buy Eggs". Home and Garden Bulletin (264). United States Department of Agriculture (USDA): 1. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ Howe, Juliette C.; Williams, Juhi R.; Holden, Joanne M. (March 2004). "USDA Database for the Choline Content of Common Foods" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 December 2010.

- ^ "Full Report (All Nutrients): 01129, Egg, whole, cooked, hard-boiled"[dead link], USDA Branded Food Products Database

- ^ "Full Report (All Nutrients): 45174951, EGGS"[dead link], USDA Branded Food Products Database

- ^ Coorey R, Novinda A, Williams H, Jayasena V (2015). "Omega-3 fatty acid profile of eggs from laying hens fed diets supplemented with chia, fish oil, and flaxseed". J Food Sci. 80 (1): S180–7. doi:10.1111/1750-3841.12735. PMID 25557903.

- ^ Anderson KE (2011). "Comparison of fatty acid, cholesterol, and vitamin A and E composition in eggs from hens housed in conventional cage and range production facilities". Poultry Science. 90 (7): 1600–1608. doi:10.3382/ps.2010-01289. PMID 21673178.

- ^ Karsten HD; et al. (2010). "Vitamins A, E and fatty acid composition of the eggs of caged hens and pastured hens". Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems. 25: 45–54. doi:10.1017/S1742170509990214. S2CID 33668490.

- ^ Jones, Deana; Musgrove, Michael; Anderson, K. E.; Thesmar, H. S. (2010). "Physical quality and composition of retail shell eggs". Poultry Science. 89 (3): 582–587. doi:10.3382/ps.2009-00315. PMID 20181877.

- ^ Evenepoel, P; Geypens B; Luypaerts A; et al. (October 1998). "Digestibility of cooked and raw egg protein in humans as assessed by stable isotope techniques". The Journal of Nutrition. 128 (10): 1716–1722. doi:10.1093/jn/128.10.1716. PMID 9772141.

- ^ a b "Eggs – No Yolking Matter Archived 9 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine." Nutrition Action Health Letter, July/August 1997.

- ^ "Egg, whole, raw, fresh per 100 g". FoodData Central, US Department of Agriculture. 1 April 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ "Egg, white, raw, fresh per 100 g". FoodData Central, US Department of Agriculture. 1 April 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ Weggemans RM, Zock PL, Katan MB (2001). "Dietary cholesterol from eggs increases the ratio of total cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in humans: a meta-analysis". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 73 (5): 885–91. doi:10.1093/ajcn/73.5.885. PMID 11333841.

- ^ Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Rimm EB, et al. (1999). "A prospective study of egg consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease in men and women". JAMA. 281 (15): 1387–94. doi:10.1001/jama.281.15.1387. PMID 10217054.

- ^ a b Li, Y; Zhou, C; Zhou, X; Li, L (2013). "Egg consumption and risk of cardiovascular diseases and diabetes: a meta-analysis". Atherosclerosis. 229 (2): 524–530. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.04.003. PMID 23643053.

- ^ a b Shin JY, Xun P, Nakamura Y, He K (July 2013). "Egg consumption in relation to risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Am J Clin Nutr. 98 (1): 146–59. doi:10.3945/ajcn.112.051318. PMC 3683816. PMID 23676423.

- ^ Tamez M, Virtanen J, Lajous M (2016). "Egg consumption and risk of incident type 2 diabetes: a dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies". British Journal of Nutrition. 15 (12): 2212–2218. doi:10.1017/S000711451600146X. PMID 27108219.

- ^ Drouin-Chartier JP, Schwab AL, Chen S, et al. (2020). "Egg consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: findings from 3 large US cohort studies of men and women and a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 112 (3): 619–630. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqaa115. PMC 7458776. PMID 32453379.

- ^ Keum N, Lee DH, Marchand N, Oh H, Liu H, Aune D, Greenwood DC, Giovannucci EL (2015). "Egg intake and cancers of the breast, ovary and prostate: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective observational studies". British Journal of Nutrition. 114 (7): 1099–107. doi:10.1017/S0007114515002135. hdl:10044/1/48759. PMID 26293984. S2CID 31168561.

- ^ Zeng ST, Guo L, Liu SK, et al. (2015). "Egg consumption is associated with increased risk of ovarian cancer: Evidence from a meta-analysis of observational studies". Clinical Nutrition. 34 (4): 635–641. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2014.07.009. PMID 25108572.

- ^ Aminianfar A, Fallah-Moshkani R, Salari-Moghaddam A, et al. (2019). "Egg Consumption and Risk of Upper Aero-Digestive Tract Cancers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies". Advances in Nutrition. 10 (4): 660–672. doi:10.1093/advances/nmz010. PMC 6628841. PMID 31041448.

- ^ Kazemi A, Barati-Boldaji R, Soltani S, et al. (2021). "Intake of Various Food Groups and Risk of Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies". Advances in Nutrition. 12 (3): 809–849. doi:10.1093/advances/nmaa147. PMC 8166564. PMID 33271590.

- ^ Tanha K, Mottaghi A, Nojomi M, Moradi M, Rajabzadeh R, Lotfi S, Janani L (2021). "Investigation on factors associated with ovarian cancer: an umbrella review of systematic review and meta-analyses". Journal of Ovarian Research. 14 (1): 153. doi:10.1186/s13048-021-00911-z. PMC 8582179. PMID 34758846.

- ^ Krittanawong, Chayakrit; Narasimhan, Bharat; Wang, Zhen; et al. (January 2021). "Association Between Egg Consumption and Risk of Cardiovascular Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". The American Journal of Medicine. 134 (1): 76–83.e2. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.05.046. PMID 32653422. S2CID 220499217.

- ^ Zhao, Bin; Gan, Lu; Graubard, Barry I.; Männistö, Satu; Albanes, Demetrius; Huang, Jiaqi (2022). "Associations of Dietary Cholesterol, Serum Cholesterol, and Egg Consumption With Overall and Cause-Specific Mortality, and Systematic Review and Updated Meta-Analysis". Circulation. 145 (20): 1506–1520. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.057642. PMC 9134263. PMID 35360933. S2CID 247853807.

- ^ Zhang X, Lv M, Luo X (2020). "Egg consumption and health outcomes: a global evidence mapping based on an overview of systematic reviews". Annals of Translational Medicine. 8 (21): 1343. doi:10.21037/atm-20-4243. PMC 7723562. PMID 33313088.

- ^ Rouhani MH, Rashidi-Pourfard N, Salehi-Abargouei A, et al. (2018). "Effects of Egg Consumption on Blood Lipids: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials". Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 37 (2): 99–110. doi:10.1080/07315724.2017.1366878. PMID 29111915. S2CID 33208171.

- ^ Drouin-Chartier JP, Chen S, Li Y (2020). "Egg consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease: three large prospective US cohort studies, systematic review, and updated meta-analysis". The BMJ. 368: m513. doi:10.1136/bmj.m513. PMC 7190072. PMID 32132002.

- ^ Godos J, Micek A, Brzostek T, et al. (2020). "Egg consumption and cardiovascular risk: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies". European Journal of Nutrition. 60 (4): 1833–1862. doi:10.1007/s00394-020-02345-7. ISSN 1436-6207. PMC 8137614. PMID 32865658. S2CID 221372891.

- ^ Mah E, Chen CO, Liska DJ (October 2019). "The effect of egg consumption on cardiometabolic health outcomes: an umbrella review". Public Health Nutr. 23 (5): 935–955. doi:10.1017/S1368980019002441. PMC 10200385. PMID 31599222. S2CID 204029375.

- ^ Marventano S, Godos J, Tieri M, Ghelfi F, Titta L, Lafranconi A, Gambera A, Alonzo E, Sciacca S, Buscemi S, Ray S, Del Rio D, Galvano F, Grosso G, et al. (2020). "Egg consumption and human health: an umbrella review of observational studies". International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition. 71 (3): 325–331. doi:10.1080/09637486.2019.1648388. PMID 31379223. S2CID 199437922. Archived from the original on 24 September 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ Rong, Ying; Chen, Li; Tingting, Zhu; et al. (2013). "Egg consumption and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies". British Medical Journal. 346 (e8539): e8539. doi:10.1136/bmj.e8539. PMC 3538567. PMID 23295181.

- ^ "No link between eggs and heart disease or stroke, says BMJ meta-analysis". 25 January 2013. Archived from the original on 19 February 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Patterson, Kristine. "USDA Database for the Choline Content of Common Foods" (PDF). U.S. Department of Agriculture. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ^ Wang, Zeneng (7 April 2011). "Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease". Nature. 472 (7341): 57–65. Bibcode:2011Natur.472...57W. doi:10.1038/nature09922. PMC 3086762. PMID 21475195.

- ^ Willyard, Cassandra (30 January 2013). "Pathology: At the heart of the problem". Nature. 493 (7434): S10–S11. Bibcode:2013Natur.493S..10W. doi:10.1038/493s10a. PMID 23364764. S2CID 4355857.

- ^ Jinzhu Jia; Pan Dou; Meng Gao; et al. (September 2019). "Assessment of Causal Direction Between Gut Microbiota–Dependent Metabolites and Cardiometabolic Health: A Bidirectional Mendelian Randomization Analysis". Diabetes. 68 (9): 1747–1755. doi:10.2337/db19-0153. PMID 31167879. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ Zhang Y, Zhang DZ (2018). "Red meat, poultry, and egg consumption with the risk of hypertension: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies". Journal of Human Hypertension. 32 (7): 507–517. doi:10.1038/s41371-018-0068-8. PMID 29725070. S2CID 19187913. Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ Kolahdouz-Mohammadi R, Malekahmadi M, Clayton ZS, Sadat SZ, Pahlavani N, Sikaroudi MK, Soltani S (2020). "Effect of Egg Consumption on Blood Pressure: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials". Current Hypertension Reports. 22 (3): 24. doi:10.1007/s11906-020-1029-5. PMC 7189334. PMID 32114646.

- ^ Alexander DD, Miller PE, Vargas AJ, Weed DL, Cohen SS (2016). "Meta-analysis of Egg Consumption and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease and Stroke". Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 35 (8): 704–716. doi:10.1080/07315724.2016.1152928. PMID 27710205. S2CID 37407829.

- ^ Bechthold A, Boeing H, Schwedhelm C, et al. (2019). "Food groups and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke and heart failure: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 59 (7): 1071–1090. doi:10.1080/10408398.2017.1392288. hdl:1854/LU-8542107. PMID 29039970. S2CID 38637145. Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ Godos J, Micek A, Brzostek T, Toledo E, Iacoviello L, Astrup A, Franco OH, Galvano F, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Grosso G (2021). "Egg consumption and cardiovascular risk: a dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies". European Journal of Nutrition. 60 (4): 1833–1862. doi:10.1007/s00394-020-02345-7. ISSN 1436-6207. PMC 8137614. PMID 32865658.

- ^ Sajadi Hezaveh Z, Sikaroudi MK, Vafa M, Clayton ZS, Soltani S (2019). "Effect of egg consumption on inflammatory markers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 99 (15): 6663–6670. Bibcode:2019JSFA...99.6663S. doi:10.1002/jsfa.9903. PMC 7189602. PMID 31259415.

- ^ Khalighi Sikaroudi M, Saraf-Bank S, Clayton ZS, Soltani S (2021). "A positive effect of egg consumption on macular pigment and healthy vision: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials". J Sci Food Agric. 101 (10): 4003–4009. Bibcode:2021JSFA..101.4003K. doi:10.1002/jsfa.11109. PMID 33491232. S2CID 231700748.

- ^ Kimura, Akiko C.; Reddy, V; Marcus, R; et al. (2004). "Chicken Consumption Is a Newly Identified Risk Factor for Sporadic Salmonella enterica Serotype Enteritidis Infections in the United States: A Case-Control Study in FoodNet Sites". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 38: S244–S252. doi:10.1086/381576. PMID 15095196.

- ^ Little, C.L; Surman-Lee, S; Greenwood, M; et al. (2007). "Public health investigations of Salmonella Enteritidis in catering raw shell eggs, 2002–2004". Letters in Applied Microbiology. 44 (6): 595–601. doi:10.1111/j.1472-765X.2007.02131.x. PMID 17576219. S2CID 19995946.

- ^ Stephens, N.; Sault, C; Firestone, SM; et al. (2007). "Large outbreaks of Salmonella Typhimurium phage type 135 infections associated with the consumption of products containing raw egg in Tasmania". Communicable Diseases Intelligence. 31 (1): 118–24. PMID 17503652.

- ^ Knowledge Guide Archived 6 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine, British Egg Information Service. Retrieved 26 February 2010.

- ^ Lion Code of Practice. Retrieved 26 February 2010.

- ^ Farming UK news article Archived 10 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 26 February 2010.

- ^ Daniel Boffey (3 August 2017). "Millions of eggs removed from European shelves over toxicity fears". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ Egg Allergy Brochure Archived 25 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine, distributed by Royal Prince Alfred Hospital

- ^ "Egg Allergy Facts" Archived 12 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America

- ^ a b Arnaldo Cantani (2008). Pediatric Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Berlin: Springer. pp. 710–713. ISBN 978-3-540-20768-9.

- ^ "Food allergen labelling and information requirements under the EU Food Information for Consumers Regulation No. 1169/2011: Technical Guidance" Archived 7 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine (April 2015).

- ^ "Requirements for the Egg Industry in the 2001 Welfare Code". Archived from the original on 30 March 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ^ Merwin, Hugh (25 November 2014). "Noticed November 25, 2014 10:00 a.m. You Can Now Buy Double-Yolk Eggs by the Dozen". Grub Street. Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ Willard, L. F. (1 August 2022). "Are Brown Eggs the Only Local Eggs?". New England. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ Blue eggs, sometimes thought a joke, are a reality, as reported here [1], for example.

- ^ See New York Times historical archive Archived 25 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine for details – link opens on correct page.

- ^ a b "A Blue Story". New Scientist. Vol. 69, no. 989. 26 February 1976. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ Evidence cited here [2].

- ^ El-banna company website, product information, available here [3] Archived 17 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Results of the study are published here Archived 11 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Virtually any on-line chicken supply company will state the egg color of each breed supplied. This Archived 28 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine is one example.

- ^ "Eggs and Egg Colour Chart". The Marans Club. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ^ "Scientists and Experts on Battery Cages and Laying Hen Welfare". Hsus.org. Archived from the original on 1 May 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ "Eggs and force-moulting". Ianrpubs.unl.edu. Archived from the original on 19 October 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ "Commercial Egg Production and Processing". Ag.ansc.purdue.edu. Archived from the original on 12 October 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ "Egg laying and male birds". Vegsoc.org. Archived from the original on 6 December 1998. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ "Free-range eggs". Cok.net. Archived from the original on 24 January 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ "United Egg Producers Certified". 8 January 2008. Archived from the original on 8 January 2008. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ "Wondering What The "UEP Certified" Logo Means?". Hsus.org. Archived from the original on 18 May 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ "Egg Labels". EggIndustry.com. Archived from the original on 4 September 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ The Humane Society of the United States. "A Brief Guide to Egg Carton Labels and Their Relevance to Animal Welfare". Hsus.org. Archived from the original on 18 May 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ "EUR-Lex – 31999L0074 – EN". Eur-lex.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ Vegetarian Society. "Egg Production & Welfare". Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ Torrella, Kenny (1 May 2023). "Save the male chicks". Vox. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ^ Blond, Josie Le (22 December 2018). "World's first no-kill eggs go on sale in Berlin". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ^ "In-Ovo Sexing Overview". Innovate Animal Ag. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Hall, Stephanie (6 April 2017). "The Ancient Art of Decorating Eggs | Folklife Today". The Library of Congress. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ Luke 11:12

- ^ "History of the Hunt: How an Easter Tradition Was Hatched". English Heritage. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ Bociąga, Przemysław (7 April 2023). "A Worldwide Easter Tradition With Central European Roots". 3 Seas Europe. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ "Dancing eggs for Corpus Christi | Barcelona Cultura". www.barcelona.cat. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ Pomranz, Mike (13 February 2018). "Fake Chinese Eggs Are a Big Problem in India: And they're scarily convincing". MyRecipes. Retrieved 20 April 2024.

- ^ Boehler, Patrick (6 November 2012). "Bad Eggs: Another Fake-Food Scandal Rocks China". Time. Retrieved 20 April 2024.

- ^ LaFraniere, Sharon (7 May 2011). "In China, Fear of Fake Eggs and 'Recycled' Buns". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 April 2024.

- ^ Wilson, Bee (16 June 2020). Swindled: The Dark History of Food Fraud, from Poisoned Candy to Counterfeit Coffee. Princeton University Press. pp. 313–314. ISBN 978-0-691-21408-5. Retrieved 20 April 2024.

- ^ Roberts, Michael T. (8 January 2016). Food Law in the United States. Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-107-11760-0.

External links

- Fact Sheet on FDA's Proposed Regulation: Prevention of Salmonella Enteritidis in Shell Eggs During Production (archived 17 June 2008)

- Egg Information U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2011)

- Egg Basics for the Consumer: Packaging, Storage, and Nutritional Information Archived 25 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine. (2007) University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources. Retrieved 23 May 2014.