Seoul

Seoul

서울 | |

|---|---|

| Seoul Special Metropolitan City 서울특별시 | |

| transcription(s) | |

| • Hangul | 서울특별시 |

| • Hanja[a] | 서울特別市 |

| • Revised Romanisation | Seoul-Teukbyeolsi |

| • McCune–Reischauer | Sŏul-T'ŭkpyŏlsi |

| Motto(s): "Seoul, my soul"[1] | |

| Anthem: none[2] | |

| Coordinates: 37°34′N 126°59′E / 37.567°N 126.983°E | |

| Country | South Korea |

| Area | Seoul Capital |

| Founded by | Taejo of Joseon |

| Districts | 25 districts |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Body | Seoul Metropolitan Government Seoul Metropolitan Council |

| • Mayor | Oh Se-hoon (People Power) |

| • National Assembly | 49 |

| Area | |

| 605.21 km2 (233.67 sq mi) | |

| • Metro | 12,685 km2 (4,898 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 38 m (125 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 836.5 m (2,744.4 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2Q 2023)[4] | |

| 9,659,322 | |

| • Rank | 1st |

| • Density | 16,000/km2 (41,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 26,037,000 |

| • Metro density | 2,053/km2 (5,320/sq mi) |

| • Demonym | Seoulite |

| • Dialect | Gyeonggi |

| GDP | |

| • Special metropolitan city | KR₩ 486 trillion (US$ 389 billion) |

| • Metro | KR₩ 1,137 trillion (US$ 910 billion) |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (Korean Standard Time) |

| ISO 3166 code | KR-11 |

| Bird | Korean magpie |

| Color | Seoul Red[6] |

| Flower | Forsythia |

| Font | Seoul fonts (Seoul Hangang and Seoul Namsan)[7] |

| Mascot | Haechi |

| Tree | Ginkgo |

| Website | seoul.go.kr |

Seoul,[b] officially Seoul Special Metropolitan City,[c] is the capital and largest city of South Korea. The broader Seoul Capital Area, encompassing Gyeonggi Province and Incheon, emerged as the world's sixth largest metropolitan economy in 2022, trailing behind Paris, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Tokyo, and New York, and hosts more than half of South Korea's population. Although Seoul's population peaked at over 10 million, it has gradually decreased since 2014, standing at about 9.6 million residents as of 2024.[8] Seoul is the seat of the South Korean government.

Seoul's history traces back to 18 BC when it was founded by the people of Baekje, one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea. During the Joseon dynasty, Seoul was officially designated as the capital, surrounded by the Fortress Wall of Seoul. In the early 20th century, Seoul was occupied by the Japanese Empire, temporarily renamed "Keijō" ("Gyeongseong" in Korean). The Korean War brought fierce battles, with Seoul changing hands four times and leaving the city mostly in ruins. Nevertheless, the city has since undergone significant reconstruction and rapid urbanization.

Seoul was rated Asia's most livable city, with the second-highest quality of life globally according to Arcadis in 2015[citation needed] and a GDP per capita (PPP) of approximately $40,000.[citation needed] 15 Fortune Global 500 companies, including industry giants such as Samsung,[9] LG, and Hyundai, are headquartered in the Seoul Capital Area, which has major technology hubs, such as Gangnam and Digital Media City.[10] Seoul is ranked seventh in the Global Power City Index and the Global Financial Centres Index, and is one of the five leading hosts of global conferences.[11] The city has also hosted major events such as the 1986 Asian Games, the 1988 Summer Olympics, and the 2010 G20 Seoul summit, in addition to three matches at the 2002 FIFA World Cup.

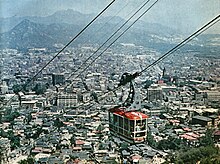

Seoul is geographically set in a mountainous and hilly terrain, with Bukhansan positioned on its northern edge. Within the Seoul Capital Area lie five UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Changdeokgung, Hwaseong Fortress, Jongmyo, Namhansanseong, and the Royal Tombs of the Joseon dynasty.[12] Furthermore, Seoul has witnessed a surge in modern architectural development, with iconic landmarks including the N Seoul Tower, the 63 Building, the Lotte World Tower, the Dongdaemun Design Plaza, Lotte World, the Trade Tower, COEX, IFC Seoul, and Parc1. Seoul was named the World Design Capital in 2010 and has served as the national hub for the music, entertainment, and cultural industries that have propelled K-pop and the Korean Wave to international prominence.

Toponymy

Traditionally, seoul (서울) has been a native Korean (as opposed to Sino-Korean) common noun simply meaning 'capital city.' The word seoul is believed to have descended from Seorabeol (서라벌; historically transliterated into the Hanja form 徐羅伐), which originally referred to Gyeongju, the capital of Silla.[13][14]

Wiryeseong (위례성; 慰禮城), the capital settlement of Baekje, was located within the boundaries of modern-day Seoul. Seoul was also known by other various historical names, such as Bukhansan-gun (북한산군; 北漢山郡, during the Goguryeo era), Namcheon (남천; 南川,[15] during the Silla era), Hanyang (한양; 漢陽, during the Northern and Southern States period), Namgyeong (남경; 南京, during the Goryeo era), and Hanseong (한성; 漢城, during the Joseon era). The word seoul was used colloquially to refer to the capital as early as the 17th century.[16] Thus, the Joseon capital of Hanseong was widely referred to as the seoul.[17] Due to its common usage, French missionaries called the Joseon capital Séoul (/se.ul/) in their writings, hence the common romanization Seoul in various languages today.

Under subsequent Japanese colonization, Hanseong was renamed as Keijō (京城, literally 'capital city')[d] by the Imperial authorities to prevent confusion with the Hanja '漢' (a transliteration of a native Korean word 한; han; lit. great), which may also refer to the Han people or the Han dynasty in Chinese and is associated with 'China' in Japanese context.[18] After World War II and the liberation of Korea, Seoul became the official name for the Korean capital. The Standard Korean Language Dictionary still acknowledges both common and proper noun definitions of seoul.[19]

Unlike most place names in Korea, as it is not a Sino-Korean word, 'Seoul' has no inherently corresponding Hanja (Chinese characters used in the Korean language). Instead of phonetically transcribing 'Seoul' to Chinese, in the Chinese-speaking world, Seoul was called Hànchéng (汉城; 漢城), which is the Chinese pronunciation of Hanseong. On 18 January 2005, the Seoul Metropolitan Government changed Seoul's official Chinese name from the historic Hànchéng to Shǒu'ěr (首尔; 首爾). Shǒu'ěr is a phono-semantic match incorporating both sound and meaning (through 首 meaning 'head', 'chief', 'first').[20][21]

History

Prehistory

There is evidence of human habitation in the area now corresponding to Seoul from 30,000 to 40,000 years before the present.[22] Around 4,000 B.C., people of the area lived in huts with lowered floors called umjip. There is evidence of the consumption of cooked grain and fish by 3,000 B.C. Around 1,500 B.C., communities began transitioning into the Bronze Age and farming at scale.[23]

Due to modern Seoul's significant urbanization, Amsa-dong Neolithic Site is the only known major archaeological site in Seoul where Stone Age materials have been found,[24] although such materials have also been found in minor sites throughout the city (and all around the surrounding Han River basin),[25] often through rescue archaeology.[26]

Samhan and Baekje periods

Around the collapse of Wiman Joseon (194–108 B.C.) in the northern part of Korea, numerous refugees went south to the Han River basin, which was then controlled by Jin (4th–2nd century B.C.). These diverse peoples brought with them culture and technology of the Chinese Warring States that accelerated the region's progress into the Iron Age. Their arrival destabilized the region; Jin disintegrated, and dozens of statelets emerged that competed for influence in the Han River basin.[27]

Baekje (18 B.C. – 660 A.D.), once one of the statelets in the Mahan confederacy, became the dominant local power by the 2nd century A.D.[28] Its capital was in Wiryeseong; Wiryeseong's specific location is not known with certainty, but it is believed to have been within the bounds of the ramparts Pungnaptoseong and Mongchontoseong.[29] This area is now in southeastern Seoul.[30][31]

Silla period

In July or August 553, Silla took the control of the region from Baekje, and the city became a part of newly established Sin Province (신주; 新州).[32][33] Sin (新) has both meaning of "New" and "Silla", thus literally means New Silla Province.

In November 555, Jinheung Taewang made a royal visit to Bukhansan, and inspected the frontier.[34] In 557, Silla abolished Sin Province, and established Bukhansan Province (북한산주; 北漢山州).[35] The word Hanseong (한성; 漢城; lit. Han Fortress) appears on the stone wall of "Pyongyang Fortress", which was presumably built in the mid to late 6th century AD over period of 42 years, located in Pyongyang, while there is no evidence that Seoul had name Hanseong dating the three kingdoms and earlier period.[36][37][38][39][40]

In 568, Jinheung Taewang made another royal visit to the northern border, visited Hanseong, and stayed in Namcheon on his way back to the capital. During his stay, he set Jinheung Taewang Stele, abolished Bukhansan Province, and established Namcheon Province (남천주; 南川州; South River Province), appointing the city as the provincial capital.[15][41] Based on the naming system, the actual name of Han River during this time was likely Namcheon (Nam River) itself or should have the word ending with "cheon" (천; 川) not "gang" (강; 江) nor "su" (수; 水). In addition, "Bukhansan" Jinheung Stele clearly states that Silla had possession of Hanseong (modern day Pyongyang), thus Bukhansan has to be located north of Hanseong. Modern day Pyongyang was not Pyongyang, Taedong River was likely Han River, and Bukhansan was not Bukhansan during the three kingdoms period.[15][42] Moreover, Pyongyang was a common noun meaning capital used by Goguryeo and Goryeo dynasties, similar to Seoul.[43]

In 603, Goguryeo attacked Bukhansanseong, which Silla ended up winning.[44][45] In 604, Silla abolished Namcheon Province, and reestablished Bukhansan Province in order to strengthen the northern border. The city lost its provincial capital position and was put under Bukhansan Province once again.[46] This further proves that Bukhansan was located in the North of modern-day Pyongyang as changing the provincial name and objective would not be required if Bukhansan was located within Seoul.

In the 11th century Goryeo, which succeeded Unified Silla, built a summer palace in Seoul, which was referred to as the "Southern Capital". It was only from this period that Seoul became a larger settlement.[47]

Joseon dynasty

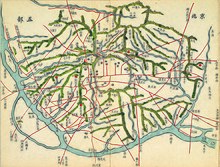

Seoul became the planned capital of Korea by Yi Seong-gye, the founding father of the Joseon dynasty. After enthroning himself as King at the capital of old Goryeo in 1392, Yi Seong-gye changed the name of his Kingdom from Goryeo to Joseon in 1393 and began his search for a place for a new capital. After several governmental debates, Yi Seong-gye chose Hanyang (Sindo) instead of Muak in September 1394. As Joseon's new capital, Hanyang was planned as a geographic embodiment of Korean Confucianism. Construction of the city began in October 1394. During its early construction stages, some major palaces, including Gyeongbokgung, were finished in 1395. The Fortress Wall surrounding Hanyang was partially finished around 1396.[48]: 96–111

The city of Hanyang was governed by the Hanseongbu (한성부), an agency of the national government dedicated to affairs on the administration of the capital city. The Hanseongbu divided Hanyang into two major categories: areas inside the Fortress Wall, which were typically named Seong-jung (성중; 城中) or Doseong-an (도성 안; lit. Inside the fortress), and areas 10 Ri (Korean mile) around the Fortress Wall, which were named as Seongjeosimni (Korean: 성저십리; Hanja: 城底十里; lit. 10 Ris around the fortress). The Doseong-an area later gained the informal but popular name Sadaemun-an (사대문 안), which literally means 'areas inside of the Four Great Gates', and became the one and only downtown (city center) of Hanyang city.[49]: 90–100

In the late 19th century, after hundreds of years of isolation, Seoul opened its gates to foreigners and began modernization. Seoul became the first city in East Asia to introduce electricity in the royal palace, which was established by the Edison Illuminating Company.[50] A decade later the city also implemented electrical street lights.[51]

Korean Empire

After Gojong's proclamation of Korea as the Korean Empire in 1897, Seoul was temporarily called Hwangseong (황성; 皇城; lit. the imperial city). Much of modern development around this era was propelled by trade with foreign countries like France and the United States. For example, the Seoul Electric Company, Seoul Electric Trolley Company, and Seoul Fresh Spring Water Company were all joint Korean–U.S. owned enterprises.[52]

Japanese annexation of Korea

After the annexation treaty in 1910, Japan annexed Korea and renamed the city Gyeongseong ("Kyongsong" in Korean and "Keijō" in Japanese). The city saw significant transformation under Japanese colonial rule. Imperial Japan removed the city walls, paved roads, and built Western-style buildings.

Seoul was deprived of its special status as the capital city and downsized under imperial Japan, compared to the traditional notion among people of the Joseon dynasty that Seoul included the area of approximately 4 km (2.5 miles) radius surrounding the Fortress Wall (i.e., Outer old Seoul; 성저십리; 城底十里). On October 1, 1910, Imperial Japan demoted Seoul as no different than any other city within the Gyeonggi Province. After Imperial Japan's redistricting, Seoul only included the area inside the Fortress Wall and present-day Yongsan District. In the 1930s, as part of Imperial Japan's war efforts leading up to the Second Sino-Japanese War, Yeongdeungpo District was annexed into Seoul on April 1, 1936, to function as an industrial complex for steel and other metalworking factories.

The city was liberated by U.S. forces at the end of World War II.

Contemporary history

In 1945, following the liberation from Japanese colonial rule, the American military assumed control of Korea, including its capital city, then referred to as Kyeongseongbu in line with Japanese nomenclature. The U.S. military government published the Charter of the City of Seoul in the official gazette on October 10 of the following year. The charter declared Seoul as the name of the city and established it as a municipal corporation. Seoul's status as a municipal corporation mirrored the independent cities in the United States that do not belong to any county, and Seoul was established as an independent administrative unit, separate from the existing provinces.[53] The Korean version of the Charter translated "municipal corporation" as "special free city" (특별자유시; 特別自由市),[e] which later became special metropolitan city (or special metropolitan city; 특별시) in the Local Autonomy Act of 1949.[54] Seoul has retained its status as the only special metropolitan city in South Korea (i.e., 서울특별시).[55][unreliable source?]

The City of Seoul is hereby constituted a municipal corporation to be known as SEOUL. The boundaries of the municipal corporation are the present limits of the City of Seoul consisting of the following eight districts: Chong Koo, Chong No Koo, Sur Tai Moon Koo, Tong Tai Moon Koo, Sung Tong Koo, Ma Po Koo, Yong San Koo, and Yang Doung Po Koo, and as such may be extended as provided by law.

— U.S. Army Military Government in Korea, Charter of the City of Seoul[53]

Seoul under the U.S. military government between 1945 and 1948 was much smaller than it is today. It only covered the Fortress Wall, marked by the Eight Gates, and the districts incorporated during Japanese rule to prosecute imperial Japan's war efforts.[f]

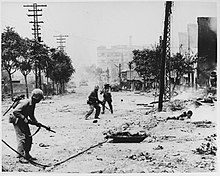

During the Korean War, Seoul changed hands between the Soviet- and Chinese-backed North Korean forces and the American-backed South Korean forces four times: falling to the North Koreans in the June 1950 First Battle of Seoul, recaptured by UN forces in the September 1950 Second Battle of Seoul, falling to a combined Chinese-North Korean force in the January 1951 Third Battle of Seoul, and finally being recaptured once more by UN forces in Operation Ripper during the spring of 1951.[56][57] The extensive fighting left the city heavily damaged after the war. The capital was temporarily relocated to Busan.[47] One estimate of the extensive damage states that after the war, at least 191,000 buildings, 55,000 houses, and 1,000 factories lay in ruins. In addition, a flood of refugees had entered Seoul during the war, swelling the population of the city and its metropolitan area to an estimated 1.5 million by 1955.[58]

Following the war, Seoul began to focus on reconstruction and modernization. As South Korea's economy started to grow rapidly from the 1960s, urbanization also accelerated and workers began to move to Seoul and other larger cities.[58] In 1963, Seoul went through two major expansions that established the shape and size of the present-day Seoul—barring minor adjustments to the borders later in 1973 and 2000. In August 1963, Seoul annexed parts of Yangju-gun, Gwangju-gun, Siheung-gun, Gimpo-gun, and Bucheon-gun, expanding the northeastern borders of Seoul. In September, Seoul again annexed present-day Gangnam.[59][60] The two consecutive expansions more than doubled the size of Seoul from approximately 268 km2 (103 sq mi) to 613 km2 (237 sq mi).[61]

After annexation, Gangnam's development was spurred by key infrastructure projects: the construction of the Hannam Bridge (1966–1969) and Gyeongbu Expressway (1968–1970). As Seoul's population kept growing, Park's regime focused its development plans on Gangnam. The main hurdle for Gangnam's development was floods because the area is low-lying and prone to flooding. Then Seoul mayor Kim Hyun-ok ordered construction of an expressway that doubled as embankment, which became the present-day Gangbyeon Expressway. The construction started in March 1967 and completed in September of the same year. Similar projects transformed previously flood-prone areas into usable land for development. Such areas include the current Ichon-dong, the Banpo apartment complex, Apgujeong-dong and Jamsil-dong.

Until 1972, Seoul was claimed by North Korea as its de jure capital, being specified as such in Article 103 of the 1948 North Korean constitution.[62]

Seoul was the host city of the 1986 Asian Games and 1988 Summer Olympics as well as one of the venues of the 2002 FIFA World Cup.

South Korea's 2019 population was estimated at 51.71 million, and according to the 2018 Population and Housing Census, 49.8% of the population resided in the Seoul metropolitan area. This was up by 0.7% from 49.1% in 2010, showing a distinct trend toward the concentration of the population in the capital.[63] Seoul has become the economic, political and cultural hub of the country,[47] with several Fortune Global 500 companies, including Samsung, SK Holdings, Hyundai, POSCO and LG Group headquartered there.[64]

Geography

Seoul is in the northwest of South Korea. Seoul proper comprises 605.25 km2 (233.69 sq mi),[3] with a radius of approximately 15 km (9 mi), roughly bisected into northern and southern halves by the Han River. The river is no longer actively used for navigation, because its estuary is located at the borders of the two Koreas, with civilian entry barred. There are four main mountains in central Seoul: Bugaksan, Inwangsan, Naksan and Namsan. The Seoul Fortress Wall, which historically bounded the city, goes over these mountains. The city is bordered by eight mountains, as well as the more level lands of the Han River plain and western areas.

Parks

Seoul has a large quantity of parks. One of the most famous parks is Namsan Park, which offers recreational hiking and views of the downtown Seoul skyline, especially via its N Seoul Tower. Seoul Olympic Park, located in Songpa District and built to host the 1988 Summer Olympics, is the largest park. The areas near the stream Tancheon are popular for exercise. Cheonggyecheon also has spaces for recreation. In 2017 the Seoullo 7017 Skypark opened, spanning diagonally overtop Seoul Station.

There are also many parks along the Han River, such as Ichon Hangang Park, Yeouido Hangang Park, Mangwon Hangang Park, Nanji Hangang Park, Banpo Hangang Park, Ttukseom Hangang Park and Jamsil Hangang Park. The Seoul National Capital Area also contains a green belt aimed at preventing the city from sprawling out into neighboring Gyeonggi Province. These areas are frequently sought after by people looking to escape from urban life on weekends and during vacations.

Air quality

Atmospheric pollution

Air pollution is a major issue in Seoul.[65][66][67][68] According to the 2016 World Health Organization Global Urban Ambient Air Pollution Database,[69] the annual average PM2.5 concentration in 2014 was 24 micrograms per cubic meter (1.0×10−5 gr/cu ft), which is 2.4 times higher than that recommended by the WHO Air Quality Guidelines[70] for the annual mean PM2.5. The Seoul Metropolitan Government monitors and publicly shares real-time air quality data.[71]

Since the early 1960s, the Ministry of Environment has implemented a range of policies and air pollutant standards to improve and manage air quality for its people.[72] The "Special Act on the Improvement of Air Quality in the Seoul Metropolitan Area" was passed in December 2003. Its 1st Seoul Metropolitan Air Quality Improvement Plan (2005–2014) focused on improving the concentrations of PM10 and nitrogen dioxide by reducing emissions.[73] As a result, the annual average PM10 concentrations decreased from 70.0 μg/m3 in 2001 to 44.4 μg/m3 in 2011[74] and 46 μg/m3 in 2014.[69] As of 2014, the annual average PM10 concentration was still at least twice than that recommended by the WHO Air Quality Guidelines.[70] The 2nd Seoul Metropolitan Air Quality Improvement Plan (2015–2024) added PM2.5 and ozone to its list of managed pollutants.[75]

Investment in air quality improvement between 2007 and 2020 in the order of US$9 billion on the part of three key local authorities, namely Gyeonggi, Incheon and Seoul, delivered a clear legal framework of responsibility, publicly checkable results and a major focus on reduction of transport pollutants.[76] In July 2020, South Korea, then the 11th largest world economy, announced a US$35 billion position on ending investment in coal.[77] In November 2020, South Korea committed to a carbon-neutral economy by 2050.[78] Between 2005 and 2021 annual concentration levels of small particulate matter (PM10) fell by 30-40 % in Seoul, whilst concentrations of larger particulate matter (PM 2.5) in the same period fell by 19% across the country and more in Seoul and Gyeonggi.[79]

Asian dust, emissions from Seoul and in general from the rest of South Korea, as well as emissions from China, all contribute to Seoul's air quality.[66][80] Besides air quality, greenhouse gas emissions represent hot issues in South Korea since the country is among top-10 strongest emitters in the world. Seoul is the strongest hotspot of greenhouse gas emissions in the country and according to satellite data, the persistent carbon dioxide anomaly over the city is one of the strongest in the world.[81] Air quality is monitored by geo-stationary satellite measurements centred on Korea and its immediate neighbours.[82]

Air pollution inside the Metro system

In January 2024 Seoul Metro, whose passengers at the time numbered approximately 7 million a day, announced plans for extensive pollution reduction measures across the network. The target was to cut pollution to over 30% below the legal limit of 50 μg/m3. It was 32 μg/m3 by 2026. The outset actuality was 38.8 μg/m3 average concentration of pollution. Starting in 2024, ₩100 billion annually for three years was earmarked for air pollution reduction measures. These included installation of air conditioning, better ventilation systems and filters, replacement of dust-inducing gravel rail tunnel beds with concrete ones, dust-capture matting at turnstiles, and constant public readings for pollution within the system.[83]

Climate

Seoul has a humid continental (Köppen: Dwa) or humid subtropical climate (Cwa, by −3 °C or 26.6 °F isotherm), influenced by the monsoons; there is great variation in temperature and precipitation throughout the year.[84][85] The suburbs of Seoul are generally cooler than the center of Seoul because of the urban heat island effect.[86] Summers are hot and humid, with the East Asian monsoon taking place from June until September. August, the hottest month, has average high and low temperatures of 30.0 and 22.9 °C (86 and 73 °F) with higher temperatures possible. Heat index values can surpass 40 °C (104.0 °F) at the height of summer. Winters are usually cold to freezing with average January high and low temperatures of 2.1 and −5.5 °C (35.8 and 22.1 °F), and are generally much drier than summers, with an average of 24.9 days of snow annually. Sometimes, temperatures drop dramatically to below −10 °C (14 °F), and on some occasions as low as −15 °C (5 °F) in the mid winter period of January and February. Temperatures below −20 °C (−4 °F) have been recorded.

| Climate data for Seoul (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1907–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.4 (57.9) |

18.7 (65.7) |

25.1 (77.2) |

29.8 (85.6) |

34.4 (93.9) |

37.2 (99.0) |

38.4 (101.1) |

39.6 (103.3) |

35.1 (95.2) |

30.1 (86.2) |

25.9 (78.6) |

17.7 (63.9) |

39.6 (103.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 2.1 (35.8) |

5.1 (41.2) |

11.0 (51.8) |

17.9 (64.2) |

23.6 (74.5) |

27.6 (81.7) |

29.0 (84.2) |

30.0 (86.0) |

26.2 (79.2) |

20.2 (68.4) |

11.9 (53.4) |

4.2 (39.6) |

17.4 (63.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −2.0 (28.4) |

0.7 (33.3) |

6.1 (43.0) |

12.6 (54.7) |

18.2 (64.8) |

22.7 (72.9) |

25.3 (77.5) |

26.1 (79.0) |

21.7 (71.1) |

15.0 (59.0) |

7.5 (45.5) |

0.2 (32.4) |

12.8 (55.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −5.5 (22.1) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

1.9 (35.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

13.5 (56.3) |

18.7 (65.7) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.9 (73.2) |

17.7 (63.9) |

10.6 (51.1) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

8.9 (48.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −22.5 (−8.5) |

−19.6 (−3.3) |

−14.1 (6.6) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

2.4 (36.3) |

8.8 (47.8) |

12.9 (55.2) |

13.5 (56.3) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

−11.9 (10.6) |

−23.1 (−9.6) |

−23.1 (−9.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 16.8 (0.66) |

28.2 (1.11) |

36.9 (1.45) |

72.9 (2.87) |

103.6 (4.08) |

129.5 (5.10) |

414.4 (16.31) |

348.2 (13.71) |

141.5 (5.57) |

52.2 (2.06) |

51.1 (2.01) |

22.6 (0.89) |

1,417.9 (55.82) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 6.1 | 5.8 | 7.0 | 8.4 | 8.6 | 9.9 | 16.3 | 14.7 | 9.1 | 6.1 | 8.8 | 7.8 | 108.6 |

| Average snowy days | 7.1 | 5.1 | 2.8 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.3 | 6.4 | 23.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 56.2 | 54.6 | 54.6 | 54.8 | 59.7 | 65.7 | 76.2 | 73.5 | 66.4 | 61.8 | 60.4 | 57.8 | 61.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 169.6 | 170.8 | 198.2 | 206.3 | 223.0 | 189.1 | 123.6 | 156.1 | 179.7 | 206.5 | 157.3 | 162.9 | 2,143.1 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 52.3 | 53.6 | 51.0 | 51.9 | 48.4 | 41.2 | 26.8 | 36.2 | 47.2 | 57.1 | 50.2 | 51.1 | 46.4 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| Source 1: Korea Meteorological Administration (percent sunshine 1981–2010)[87][88][89] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (UV),[90] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[91] | |||||||||||||

Government

The Seoul Metropolitan Government is the local government for Seoul, and is responsible for the administration and provision of various services to the city, including correctional institutions, education, libraries, public safety, recreational facilities, sanitation, water supply, and welfare services. It is headed by a mayor and three vice mayors, and is divided into 25 autonomous districts and 522 administrative neighborhoods.[92][93]

Administrative districts

Seoul is divided into 25 "gu" (구; 區) (district).[94] The gu vary greatly in area (from 10 to 47 km2 or 3.9 to 18.1 sq mi) and population (from fewer than 140,000 to 630,000). Songpa has the most people, while Seocho has the largest area. The government of each gu handles many of the functions that are handled by city governments in other jurisdictions. Each gu is divided into "dong" (동; 洞), or neighborhoods. Some gu have only a few dongs while others like Jongno District have a very large number of distinct neighborhoods. Seoul has 423 administrative dongs (행정동) in total.[94]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1949 | 1,437,670 | — |

| 1960 | 2,445,402 | +70.1% |

| 1970 | 5,433,198 | +122.2% |

| 1980 | 8,364,379 | +53.9% |

| 1990 | 10,612,577 | +26.9% |

| 2000 | 9,895,217 | −6.8% |

| 2010 | 9,794,304 | −1.0% |

| 2020 | 9,586,195 | −2.1% |

| Source: [95] | ||

Seoul proper is noted for its population density, which is almost twice that of New York City and eight times greater than Rome. Its metropolitan area was the most densely populated among OECD countries in Asia in 2012, and second worldwide after that of Paris.[96] As of the end of June 2011, 10.29 million Republic of Korea citizens lived in the city. This was a 0.24% decrease from the end of 2010. The population was 10.44 million in 2012, and 9.86 million in 2015.[97] As of 2021, Seoul's population is 9.59 million.[98][99] The population of Seoul has been dropping since the early 1990s, the reasons being the high costs of living, urban sprawling to Gyeonggi region's satellite bed cities and an aging population.[97]

As of 2016, the number of foreigners living in Seoul was 404,037, 22.9% of the total foreign population in South Korea.[100] As of June 2011, 186,631 foreigners were Chinese citizens of Korean ancestry. This was an 8.84% increase from the end of 2010 and a 12.85% increase from June 2010. The next largest group was Chinese citizens who were not of Korean ethnicity; 29,901 of them resided in Seoul. The next highest group consisted of the 9,999 United States citizens who were not of Korean ancestry. The next highest group were Taiwanese citizens, at 8,717.[101]

Religion

The two major religions in Seoul are Christianity and Buddhism. Other religions include Muism (indigenous religion) and Confucianism. Seoul is home to one of the world's largest Christian congregations, Yoido Full Gospel Church, which has around 830,000 members.[102] According to the 2015 census, 10.8% of the population follows Buddhism and 35% follows Christianity (24.3% Protestantism and 10.7% Catholicism). 53.6% of the population is irreligious.[103] Seoul is home to the world's largest modern university founded by a Buddhist Order, Dongguk University.[104]

Education

Compulsory education lasts from grade 1–9 (six years of elementary school and three years of middle school).[105] Students spend six years in elementary school, three years in middle school, and three years in high school. Secondary schools generally require students to wear uniforms. There is an exit exam for graduating from high school and many students proceeding to the university level are required to take the College Scholastic Ability Test that is held every November. Although there is a test for non-high school graduates, called school qualification exam, most Koreans take the test.

Seoul is home to various specialized schools, including three science high schools, and six foreign language High Schools. Seoul Metropolitan Office of Education comprises 235 College-Preparatory High Schools, 80 Vocational Schools, 377 Middle Schools, and 33 Special Education Schools as of 2009[update].

Seoul is home to the majority of South Korea's most prestigious universities, including Seoul National University, Yonsei University, Korea University. Seoul ranked 2nd on the QS Best Student Cities 2023.[106]

Economy

Seoul is the business and financial hub of South Korea. Although it accounts for only 0.6 percent of the nation's land area, 48.3 percent of South Korea's bank deposits were held in Seoul in 2003,[107] and the city generated 23 percent of the country's GDP overall in 2012.[108] In 2008 the Worldwide Centers of Commerce Index ranked Seoul No.9.[109] The Global Financial Centres Index in 2015 listed Seoul as the 6th financially most competitive city in the world.[110] The Economist Intelligence Unit ranked Seoul 15th in the list of "Overall 2025 City Competitiveness" regarding future competitiveness of cities.[111]

Manufacturing

The traditional, labor-intensive manufacturing industries have been continuously replaced by information technology, electronics and assembly-type of industries;[112][113] however, food and beverage production, as well as printing and publishing remained among the core industries.[112] Major manufacturers are headquartered in the city, including Samsung, LG, Hyundai, Kia and SK. Notable food and beverage companies include Jinro, whose soju is the most sold alcoholic drink in the world, beating out Smirnoff vodka;[114] top selling beer producers Hite (merged with Jinro) and Oriental Brewery.[115] It also hosts food giants like Seoul Dairy Cooperative, Nongshim Group, Ottogi, CJ, Orion, Maeil Holdings, Namyang Dairy Products and Lotte.

Business and finance

According to the Global Financial Centerss Index report released in 2024, Seoul ranked 10th. The city ranked 13th in business environment and financial sector development, seventh in human capital, 10th in infrastructure and 12th in reputation.[116]

Seoul has three central business districts; the Downtown Seoul(CBD), Gangnam(GBD), and Yeouido(YBD).[117] The Downtown Seoul, which has 600 years of history as unparalleled business district in entire Korea, is now a densely concentrated area around Gwanghwamun and Cheonggyecheon with headquarters of major companies, foreign financial institutions, largest news agencies and law firms. Other two business districts are developed in 1970s and have different characteristic; while Gangnam is well known for tech, luxury and private education industries, Yeouido is famous for securities exchange and asset management.[118][119]

In 2023, the city announced plans to invest $44.7 million over six years to create a dedicated area to attract foreign investment.[116]

Commerce

The largest wholesale and retail market in South Korea, the Dongdaemun Market, is located in Seoul.[120] Myeongdong is a shopping and entertainment area in downtown Seoul with mid- to high-end stores, fashion boutiques and international brand outlets.[121] The nearby Namdaemun Market, named after the Namdaemun Gate, is the oldest continually running market in Seoul.[122]

Insadong is the cultural art market of Seoul, where traditional and modern Korean artworks, such as paintings, sculptures and calligraphy are sold.[123] Hwanghak-dong Flea Market and Janganpyeong Antique Market also offer antique products.[124][125] Some shops for local designers have opened in Samcheong-dong, where numerous small art galleries are located. While Itaewon had catered mainly to foreign tourists and American soldiers based in the city, Koreans now comprise the majority of visitors to the area.[126] The Gangnam district is one of the most affluent areas in Seoul[126] and is noted for the fashionable and upscale Apgujeong-dong and Cheongdam-dong areas and the COEX Mall. Wholesale markets include Noryangjin Fisheries Wholesale Market and Garak Market.

The Yongsan Electronics Market is the largest electronics market in Asia. Electronics markets are Gangbyeon station metro line 2 Techno mart, ENTER6 MALL & Shindorim station Technomart mall complex.[127] Times Square is one of Seoul's largest shopping malls, and contains the world's largest permanent 35 mm cinema screen, the CGV Starium.[128]

Korea World Trade Center Complex, which comprises COEX mall, congress center, 3 Inter-continental hotels, Business tower (Asem tower), Residence hotel, Casino and City airport terminal was established in 1988 in time for the Seoul Olympics. The 2nd World trade trade center is being planned at Seoul Olympic stadium complex as MICE HUB by Seoul. Ex-Kepco head office building was purchased by Hyundai motor group with 9billion USD to build 115-storey Hyundai GBC & hotel complex until 2021. Now ex-kepco 25-storey building is under demolition.

Technology

Seoul has been described as the world's "most wired city",[129] ranked first in technology readiness by PwC's Cities of Opportunity report.[130] Seoul has a very technologically advanced infrastructure.[131][132]

Seoul is among the world leaders in Internet connectivity, being the capital of South Korea, which has the world's highest fiber-optic broadband penetration and highest global average internet speeds of 26.1 Mbit/s.[133][134] Since 2015, Seoul has provided free Wi-Fi access in outdoor spaces through a 47.7 billion won ($44 million) project with Internet access at 10,430 parks, streets and other public places.[135] Internet speeds in some apartment buildings reach up to 52.5 Gbit/s with assistance from Nokia, and though the average standard consists of 100 Mbit/s services, providers nationwide are rapidly rolling out 1Gbit/s connections at the equivalent of US$20 per month.[136] In addition, the city is served by the KTX high-speed rail and the Seoul Subway, which provides 4G LTE, Wi-Fi, and DMB inside subway cars. 5G will be introduced commercially in March 2019 in Seoul.

Culture

Architecture

The traditional heart of Seoul is the old Joseon dynasty city, now the downtown area, where most palaces, government offices, corporate headquarters, hotels, and traditional markets are located. Cheonggyecheon, a stream that runs from west to east through the valley before emptying into the Han River, was for many years covered with concrete, but was recently restored by an urban revival project in 2005.[137] Jongno street, meaning "Bell Street", has been a principal street and one of the earliest commercial streets of the city,[138][139] on which one can find Bosingak, a pavilion containing a large bell.

Seoul has many historical and cultural landmarks. In Amsa-dong Prehistoric Settlement Site, Gangdong District, neolithic remains were excavated and accidentally discovered by a flood in 1925.[140]

Urban and civil planning was a key concept when Seoul was first designed to serve as a capital in the late 14th century. The Joseon dynasty built the "Five Grand Palaces" in Seoul—Changdeokgung, Changgyeonggung, Deoksugung, Gyeongbokgung and Gyeonghuigung—all of which are located in the Jongno and Jung Districts. Among them, Changdeokgung was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1997 as an "outstanding example of Far Eastern palace architecture and garden design". The main palace, Gyeongbokgung, underwent a large-scale restoration project.[141] Seoul has been surrounded by walls that were built to regulate visitors from other regions and protect the city in case of an invasion. Pungnap Toseong is a flat earthen wall built at the edge of the Han River, which is widely believed to be the site of Wiryeseong. Mongchon Toseong is another earthen wall built during the Baekje period that is now located inside the Olympic Park.[142] The Fortress Wall of Seoul was built early in the Joseon dynasty for protection of the city. After many centuries of destruction and rebuilding, about 2⁄3 of the wall remains, as well as six of the original eight gates. These gates include the south gate Namdaemun and the east gate Dongdaemun. Namdaemun was the oldest wooden gate until a 2008 arson attack, and was re-opened after complete restoration in 2013.[143]

Museums

Seoul is home to 115 museums,[144] including four national and nine official municipal museums. The National Museum of Korea has a collection of 220,000 artifacts.[145] The National Folk Museum is located on the grounds of Gyeongbokgung and focuses on the daily life of historical Koreans.[146] Bukchon Hanok Village and Namsangol Hanok Village are old residential districts consisting of hanok (traditional Korean houses).[147][148]

The War Memorial covers the history of wars that Korea has been involved with, especially the Korean War.[149][150] Seodaemun Prison is a former prison built during the Japanese occupation, and is used as a historic museum.[151] The Seoul Museum of Art, Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, and Ilmin Museum of Art are art museums in the city.

Festivals

In October 2012, KBS Hall in Seoul hosted major international music festivals – First ABU TV and Radio Song Festivals within frameworks of Asia-Pacific Broadcasting Union 49th General Assembly.[152][better source needed][153] Seoul Street Art Festival is a seasonal cultural festival held four times a year every spring, summer, autumn, and winter in Seoul, South Korea since 2003. It is based on the "Seoul Citizens' Day" held on every October since 1994 to commemorate the 600 years history of Seoul as the capital of the country. The festival is arranged under the Seoul Metropolitan Government. As of 2012[update], Seoul has hosted Ultra Music Festival Korea, an annual dance music festival that takes place on the 2nd weekend of June.[154]

Media

Seoul is home of the major South Korean networks KBS, SBS, and MBC. The city is also home to the major South Korean newspapers The Chosun Ilbo, The Dong-A Ilbo, JoongAng Ilbo, and Hankook Ilbo. In Seoul, there is a digital news operation for the New York Times. It can accommodate up to 50 employees. It has about 20 editors and staff.[155] The Washington Post Seoul Hub is one of the key bases of the Wall Street Journal along with that of London.[156]

Sports

Seoul is a major center of South Korean sports, and has the largest number of professional sports teams and facilities in the country. In the history of South Korea's major professional sports league championships, which include the K League, KBO League, KBL and V-League, Seoul had multiple championship winners during the same season twice; in 1990, when Lucky-Goldstar FC (currently FC Seoul) won the 1990 K League and the LG Twins won the 1990 KBO League, and in 2016, when FC Seoul won the 2016 K League Classic and the Doosan Bears won the 2016 KBO League.[157]

Seoul hosted the 1986 Asian Games, also known as Asiad, 1988 Olympic Games, and Paralympic Games. It also served as one of the host cities of the 2002 FIFA World Cup. Seoul World Cup Stadium hosted the opening ceremony and first game of the tournament. Taekwondo is South Korea's national sport and Seoul is the location of the Kukkiwon, the world headquarters of taekwondo, as well as the World Taekwondo Federation.

Transportation

Seoul has a well developed transportation network. Its system dates back to the era of the Korean Empire, when the first streetcar lines were laid and a railroad linking Seoul and Incheon was completed.[158] Seoul's most important streetcar line ran along Jongno until it was replaced by Line 1 of the subway system in the early 1970s. Other notable streets in downtown Seoul include Euljiro, Teheranno, Sejongno, Chungmuro, Yulgongno, and Toegyero. There are nine major subway lines stretching for more than 250 km (155 mi), with one additional line planned. As of 2010[update], 25% of the population has a commute time of an hour or longer.

Bus

Seoul's bus system is operated by the Seoul Metropolitan Government (S.M.G.), with four primary bus configurations available servicing most of the city. Seoul has many large intercity/express bus terminals. These buses connect Seoul with cities throughout South Korea. The Seoul Express Bus Terminal, Central City Terminal and Seoul Nambu Terminal are located in the district of Seocho District. In addition, East Seoul Bus Terminal in Gwangjin District and Sangbong Terminal in Jungnang District handles traffics mainly from Gangwon and Chungcheong provinces.

Urban rail

Seoul has a comprehensive urban railway network of 21 rapid transit, light metro and commuter lines that interconnects every district of the city and the surrounding areas of Incheon, Gyeonggi province, western Gangwon Province, and northern South Chungcheong Province. With more than 8 million passengers per day, the subway is one of the busiest subway systems in the world and the largest in the world, with a total track length of 940 km (580 mi). In addition, in order to cope with the various modes of transport, Seoul's metropolitan government employs several mathematicians to coordinate the subway, bus, and traffic schedules into one timetable. The various lines are run by Korail, Seoul Metro, NeoTrans Co. Ltd., AREX, and Seoul Metro Line 9 Corporation.

Train

Seoul is connected to every major city in South Korea by rail. Most major South Korean cities are linked via the KTX high-speed train, which has a normal operation speed of more than 300 km/h (186 mph). The Mugunghwa and Saemaeul trains also stop at all major stations. Major railroad stations include:[citation needed]

- Seoul Station, Yongsan District: Gyeongbu line (KTX/ITX-Saemaeul/Nuriro/Mugunghwa-ho)

- Yongsan station, Yongsan District: Honam line (KTX/ITX-Saemaeul/Nuriro/Mugunghwa), Jeolla/Janghang lines (Saemaul/Mugunghwa)

- Yeongdeungpo station, Yeongdeungpo District: Gyeongbu/Honam/Janghang lines (KTX/ITX-Saemaeul/Saemaul/Nuriro/Mugunghwa)

- Cheongnyangni station, Dongdaemun District: Gyeongchun/Jungang/Yeongdong/Taebaek lines (ITX-Cheongchun/ITX-Saemaeul/Mugunghwa)

- Suseo station (HSR), Gangnam District: Suseo HSR (SRT)

Airports

Seoul is served by two international airports, Incheon International Airport and Gimpo International Airport.

Gimpo International Airport opened in 1939 as an airfield for the Japanese Imperial Army and opened for civil aircraft in 1957. Since the opening of Incheon International, Gimpo International handles domestic flights along with some short haul international flights to Tokyo Haneda, Osaka Kansai, Taipei Songshan, Shanghai Hongqiao, and Beijing Capital although flights to Osaka Kansai and Beijing Capital also operate from Incheon International.

Incheon International Airport opened in March 2001 in Yeongjong island. It is now responsible for major international flights. Incheon International Airport is Asia's eighth busiest airport in terms of passengers, the world's fourth busiest airport by cargo traffic, and the world's eighth busiest airport in terms of international passengers in 2014. In 2016, 57,765,397 passengers used the airport. Incheon International Airport opened terminal 2 on 18 January 2018.

Incheon and Gimpo are linked to Seoul by expressway, and to each other by the AREX to Seoul Station. Intercity bus services are available to various destinations around the country.

Cycling

Cycling is becoming increasingly popular in Seoul and in the entire country. Both banks of the Han River have cycling paths that run all the way across the city along the river. In addition, Seoul introduced in 2015 a bicycle-sharing system named Ddareungi (and named Seoul Bike in English).[159]

International relations

Seoul is a member of the Asian Network of Major Cities 21 and the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group. In addition, Seoul hosts many embassies of countries it has diplomatic ties with.

Sister cities

See also

- Geography of South Korea

- List of cities in South Korea

- List of most populous cities

- List of tallest buildings in Seoul

- Economy of Seoul

Notes

- ^ Seoul has no Hanja-derived names. The official Chinese translation of the city is Shou'er, based on its pronunciation. See the toponymy section.

- ^ /soʊl/ SOHL; Korean: 서울; IPA: [sʰʌ.uɭ] ; lit. 'Capital'.

- ^ Korean: 서울특별시; RR: Seoul Teukbyeolsi.

- ^ Also referred to as Gyeongseong (경성; 京城) via its Korean pronunciation.

- ^ As written in the Korean version of the charter:

第一條 「京城府」를「서울市」라稱하고此를特別自由市로함

— Official Gazette, USAMGIK Charter City of Seoul[53] - ^ Notably, Yeongdeungpo District was incorporated into Kyeongseong (or Keijō) and developed under imperial Japan as a major industrial complex.

References

- ^ ""Seoul, my soul" selected as the city's new slogan". Seoul Metropolitan Government. 5 April 2023. Archived from the original on 7 May 2023. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ^ 서울시 사이트에 서울 시가인 서울의 찬가가 없습니다.. Seoul Metropolitan Government. Archived from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Seoul Statistics (Land Area)". Seoul Metropolitan Government. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "City Overview (Population)". Seoul Metropolitan Government. Archived from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ 2022년 지역소득(잠정). www.kostat.go.kr.

- ^ "Color". Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ^ "Seoul's symbols". Seoul Metropolitan Government. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ^ "City Overview (Population)". Seoul Metropolitan Government. Archived from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ "Samsung Electronics". Fortune. Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ^ "Tech capitals of the world". The Age. Melbourne. 15 June 2009. Archived from the original on 12 September 2009. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- ^ Union of International Associations (UIA) International Meetings Statistics for the Year 2011 Archived 3 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Joel Fischer.

- ^ "Lists: Republic of Korea". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ 정, 구복. 서울. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ Ju, Bo Don (2019). "Gyeongju, a City of History". Journal of Korean Art & Archaeology. 13: 15–23. doi:10.23158/jkaa.2019.v13_02. ISSN 2951-4983.

- ^ a b c "Monument on Bukhansan Mountain Commemorating the Border Inspection by King Jinheung of Silla". National Institute of Korean History. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ Hendrick Hamel, a 17th-century Dutch sailor who was shipwrecked on Jeju Island, referred to the Joseon capital as Sior in his book "Hamel's Journal and a Description of the Kingdom of Korea, 1653–1666." Refer to the English translation of the book on this website created by Dr. Henny Savenije, a Dutch scholar known for his research on Hamel.

- ^ Yu, Woo-ik; Lee, Chan (6 November 2019). "Seoul". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 9 June 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

The city was popularly called Seoul in Korean during both the Chosŏn (Yi) dynasty (1392–1910) and the period of Japanese rule (1910–45), although the official names in those periods were Hansŏng (Hanseong) and Kyŏngsŏng (Gyeongseong), respectively.

- ^ Kim, Dong Hoon (22 March 2017). Eclipsed Cinema: The Film Culture of Colonial Korea. ISBN 9781474421829. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ 국립국어원 표준국어대사전. Standard Korean Language Dictionary. Retrieved 13 June 2024.

- ^ 서울특별시표기 首爾로...중국, 곧 정식 사용키로 (in Korean). Naver News. 23 October 2005. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ "Chinese Naming Crisis Danger Opportunity Summer 2006 – Good Characters". goodcharacters.com. Archived from the original on 30 September 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ Seoul: A 2,000-Year History Vol. 2 2015, p. 13.

- ^ Seoul: A 2,000-Year History Vol. 2 2015, pp. 122–123, 155.

- ^ Seoul: A 2,000-Year History Vol. 2 2015, pp. 71, 121.

- ^ Seoul: A 2,000-Year History Vol. 2 2015, p. 77.

- ^ Seoul: A 2,000-Year History Vol. 2 2015, pp. 13–16, 70.

- ^ Seoul: A 2,000-Year History Vol. 3 2015, pp. 49–52, 114.

- ^ Seoul: A 2,000-Year History Vol. 3 2015, pp. 52–53, 66, 68–69.

- ^ Seoul: A 2,000-Year History Vol. 3 2015, p. 114.

- ^ Seoul: A 2,000-Year History Vol. 3 2015, p. 136.

- ^ "Pungnap-dong Toseong Fortress (서울 풍납동 토성)". VisitKorea.or.kr. Korea Tourism Organization. Retrieved 2 December 2024.

- ^ "Samguk Sagi Silla Jinheung 19". National Institute of Korean History. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Samguk Sagi Baekje Seong 19". National Institute of Korean History. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Samguk Sagi Silla Jinheung 24". National Institute of Korean History. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Samguk Sagi Silla Jinheung 28". National Institute of Korean History. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Pyongyang Fortress Stone 1". National Institute of Korean History. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Pyongyang Fortress Stone 2". National Institute of Korean History. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Pyongyang Fortress Stone 3". National Institute of Korean History. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Pyongyang Fortress Stone 4". National Institute of Korean History. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Pyongyang Fortress Stone 6". National Institute of Korean History. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Samguk Sagi Silla Jinheung 45". National Institute of Korean History. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "고구려 수도 평양은 북한땅에 없었다". 신동아 (in Korean). 22 January 2013. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ 고대 평양은 지금의 평양이 아니다. K스피릿 (in Korean). 11 July 2016. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Samguk Sagi Silla Jinpyeong 30". National Institute of Korean History. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Samguk Sagi Goguryeo Yeongyang 15". National Institute of Korean History. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Samguk Sagi Silla Jinpyeong 32". National Institute of Korean History. Archived from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ a b c "Seoul". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ 김기호; 김웅호; 염복규; 김영심; 김도연; 유승희; 박준형 (30 November 2021). 서울도시계획사 1 현대 이전의 도시계획 (서울역사총서 12) [History of urban planning in Seoul, Vol. 1., Urban planning before contemporary age] (in Korean). Seoul: Seoul Historiography Institute. ISBN 9791160711301.

- ^ 김경록; 유승희; 김경태; 이현진; 정은주; 최진아; 이민우; 진윤정 (3 June 2019). 조선시대 다스림으로 본 성저십리 (서울역사중점연구 5) [Seongjeosimni in governance of Joseon (Studies on special topics of Seoul History, Vol. 5.)] (in Korean). Seoul: Seoul Historiography Institute. ISBN 9791160710670.

- ^ Nam Moon Hyon. "Early History of Electrical Engineering in Korea: Edison and First Electric Lighting in the Kingdom of Corea" (PDF). Promoting the History of EE Jan 23–26, 2000. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Kyung Moon Hwang (2010). A History of Korea. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 142. ISBN 9780230364523. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ Chung, Young-Iob (2006). Korea under Siege, 1876–1945 : Capital Formation and Economic Transformation. Oxford University Press. p. 70. ISBN 9780198039662.

- ^ a b c 서울은 어떻게 '특별시'가 됐나…근거 문서 '서울시헌장' 공개. Seoul Historiography Institute (in Korean). 26 August 2021.

- ^ 정, 현수 (12 September 2021). 번역이 만든 '서울특별시'…서울은 어떻게 '특별한' 시가 됐나. Money Today (in Korean).

- ^ 최, 현영 (3 December 2002). 서울특별시, 광역시로 변경해야 (in Korean). OhmyNews. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- ^ "The Korean War Chronology". U.S. Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on 9 September 2023. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- ^ "Chapter XXVI: The Capture of Seoul". U.S. Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- ^ a b Stephen Hamnett, Dean Forbes, ed. (2012). Planning Asian Cities: Risks and Resilience. Routledge. p. 159. ISBN 9781136639272. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ 서울의 역사. Seoul Metropolitan Government (in Korean).

- ^ "Urban Planning of Seoul" (PDF). Seoul Metropolitan Government. 2009. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ 면적과 인구밀도. data.si.re.kr. 서울연구데이터서비스.

- ^ "Constitution of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ^ "Korean Cultural Centre India New Delhi". Korean Cultural Centre India New Delhi. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ^ "GLOBAL 500". CNNMoney. 23 July 2012. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Lee, Hyun-jeong. "Korea Wrestles with Growing Health Threat from Fined Dust" Archived 9 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Korea Herald. 23 March 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ^ a b Hu, Elise. "Korea's Air Is Dirty, But It's Not All Close-Neighbor China's Fault" Archived 9 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine. NPR. 3 June 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ^ "Seoul's smelly gingko problem". BBC News. 12 October 2015. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ "[Feature] South Korea's odor pollution problem". 3 October 2018. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ a b Global Urban Ambient Air Pollution Database. Archived 19 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine World Health Organization. May 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ^ a b WHO Air Quality Guidelines. Archived 23 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine World Health Organization. September 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ^ Air Quality Information. Archived 10 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine Seoul Metropolitan Government. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ^ Yu-Jin Choi; Woon-Soo Kim (25 June 2015). "Changes in Seoul's Air Quality Control Policy". Seoul Solution. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- ^ 1st Seoul Metropolitan Air Quality Improvement Plan. Archived 27 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine Ministry of Environment, Republic of Korea. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ Kim, Honghyok; Kim, Hyomi; Lee, Jong-Tae (2015). "Effects of ambient air particles on mortality in Seoul: Have the effects changed over time?". Environmental Research. 140: 684–690. Bibcode:2015ER....140..684K. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2015.05.029. ISSN 0013-9351. PMID 26079317.

- ^ 2nd Seoul Metropolitan Air Quality Improvement Plan. Archived 26 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine Ministry of Environment, Republic of Korea. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ "Air pollution | Smog is lifting over greater Seoul". www.unep.org. 8 January 2024. Retrieved 31 August 2024.

- ^ "Japan, Republic of Korea Pledge to Go Carbon-neutral by 2050". SDG Knowledge Hub. Retrieved 31 August 2024.

- ^ "Japan, Republic of Korea Pledge to Go Carbon-neutral by 2050". SDG Knowledge Hub. Retrieved 31 August 2024.

- ^ Environment, U. N. (16 May 2023). "Achieving clean air for blue skies in Seoul, Incheon and Gyeonggi, Republic of Korea | UNEP - UN Environment Programme". www.unep.org. Retrieved 31 August 2024.

- ^ Chung, Anna. "Korea's policy towards pollution and fine particle: a sense of urgency" Archived 27 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Korea Analysis. v2. June 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ Labzovskii, Lev; Jeong, Su-Jong; Parazoo, Nicholas C. (2019). "Working towards confident spaceborne monitoring of carbon emissions from cities using Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2". Remote Sensing of Environment. 233. 111359. Bibcode:2019RSEnv.23311359L. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2019.111359. S2CID 202176909.

- ^ Choi, Won Jun, Kyung-Jung Moon, Goo Kim, and Dongwon Lee. "Reliability Analysis Based on Air Quality Characteristics in East Asia Using Primary Data from the Test Operation of Geostationary Environment Monitoring Spectrometer (GEMS)." Atmosphere 14, no. 9 (2023): 1458.

- ^ "Seoul Metro initiates plans to reduce air pollution by over 30% -". Official Website of the. 16 January 2024. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ "Seoul, South Korea Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- ^ Peterson, Adam (31 October 2018), English: Data sources: Köppen types calculated from data from WorldClim.org, archived from the original on 10 October 2020, retrieved 9 June 2019

- ^ Lee, Sang-Hyun; Baik, Jong-Jin (1 March 2010). "Statistical and dynamical characteristics of the urban heat island intensity in Seoul". Theoretical and Applied Climatology. 100 (1–2): 227–237. Bibcode:2010ThApC.100..227L. doi:10.1007/s00704-009-0247-1. S2CID 120641921. Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ "Climatological Normals of Korea (1991 ~ 2020)" (PDF) (in Korean). Korea Meteorological Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ 순위값 - 구역별조회 (in Korean). Korea Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ "Climatological Normals of Korea" (PDF). Korea Meteorological Administration. 2011. p. 499 and 649. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ "Seoul, South Korea - Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast". Weather Atlas. Yu Media Group. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ "Station Seoul" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ 서울특별시청 Seoul Metropolitan Government (in Korean). Doosan Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2008.

- ^ "Organization Chart". Official site of Seoul Metropolitan Government. Archived from the original on 8 May 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2008.

- ^ a b "Administrative Districts". Seoul Metropolitan Government. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ "Population Census". Statistics Korea.

- ^ "Regional population density: Asia and Oceania, 2012: Inhabitants per square kilometre, TL3 regions". OECD Regions at a Glance 2013. 2013. doi:10.1787/reg_glance-2013-graph37-en. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Seoul's Population Drops Below 10 Million for First Time in 25 Years". The Chosun Ilbo. 14 February 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ 32년 만에 '1000만 서울 시대' 막 내렸다.... Hankook Ilbo (in Korean). 3 March 2021. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "Seoul Statistics (Population)". Seoul Metropolitan Government. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ^ "1.76 million foreigners live in South Korea; 3.4% of population". 17 November 2017. Archived from the original on 21 December 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ "Korean Chinese account for nearly 70% of foreigners in Seoul". The Korea Times. 11 September 2011. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ "South Korean mega-churches. For God and country". Economist. 15 October 2011. Archived from the original on 15 January 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ "2015 Census – Religion Results" (in Korean). KOSIS KOrean Statistical Information Service. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ "Dongguk University". Archived from the original on 15 September 2018.

- ^ 의무교육(무상의무교육). Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ "QS Best Student Cities 2023". Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. 29 June 2022. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ Yim, Seok-hui. "Geographical Features of Social Polarization in Seoul, South Korea" (PDF). In Mizuuchi, Toshio (ed.). Representing Local Places and Raising Voices from Below. Osaka City University. p. 34. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ^ Industrial Policy and Territorial Development: Lessons from Korea. OECD Development Center. 16 May 2012. p. 58. ISBN 9789264173897.

- ^ "Worldwide Centers of Commerce Index" (PDF). MasterCard. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 June 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ "The Global Financial Centres Index 12" (PDF). Z/Yen Group. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ "Hot Spots 2025: Benchmarking the Future Competitiveness of Cities" (PDF). The Economist Intelligence Unit. 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 January 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Seoul: Economy". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ "The primacy of Seoul and the capital region". United Nations University. Archived from the original on 4 November 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ "It's official: Jinro soju is the world's best-selling liquor". CNNTravel. 12 June 2012. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ^ "Fiery food, boring beer". The Economist. 24 November 2012. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ a b "Seoul rises one spot to 10th in Global Financial Centres Index". The Korea Herald. 21 March 2024.

- ^ "Top 3 Major Business Districts (CBD) in Seoul, Korea". pearsonkorea.com. Pearson & Partners. 25 August 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ Lee, Sue (18 March 2011). "Beginners guide to Seoul office lease". The Korea Times. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ "Neon shines brightly during the bustle on Yeouido stock street". Korea JoongAng Daily. 5 January 2010. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ "Dongdaemun Market". VisitSeoul.net. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ "Myeong-dong". Korea Tourism Organization. Archived from the original on 15 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ 서울공식여행가이드. VisitSeoul.net. Archived from the original on 14 February 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ "Insa-dong". Korea Tourism Organization. Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ "Hwanghak-dong Flea Market". Korea Tourism Organization. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ "Antique Markets". Seoul Metropolitan Government. Archived from the original on 8 October 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Itaewon: Going Gangnam Style?". The Korea Times. 14 February 2013. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ "Yongsan Electronics Market, Asia's largest IT shopping mall". KBS World. 1 March 2011. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ "Largest Permanent 35mm Cinema Screen". Guinnessworldrecords.com. 18 August 2009. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- ^ "50 reasons why Seoul is world's greatest city". 12 July 2017. Archived from the original on 22 October 2014. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ^ PricewaterhouseCoopers. "Cities of Opportunity" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 May 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^ "KOREA: Future is now for Korean info-tech". AsiaMedia. Regents of the University of California. 14 June 2005. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008.

- ^ "Tech capitals of the world – Technology". The Age. Melbourne, Australia. 18 June 2007. Archived from the original on 12 September 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^ akamai's [state of the internet] Q4 2016 report (PDF) (Report). Akamai Technologies. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ "Hi Seoul, SOUL OF ASIA – Seoul Located In the Center of Asian Metropolises". Seoul Metropolitan Government. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- ^ Wifi in All Public Areas Archived 17 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ CJ헬로비전-에러페이지. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ "Seoul's Cheonggyecheon Stream symbolizes Korea's past, present and tomorrow". Korea.net. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ Vinayak Bharne, ed. (2013). The Emerging Asian City: Concomitant Urbanities and Urbanisms. Routledge. p. 59. ISBN 9780415525978. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ Andrei Lankov (24 June 2010). "Jongno walk". The Korea Times. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ "Amsa-dong Prehistoric Settlement Site". Korea Tourism Organization. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ "About the Palace". Gyeongbokgung Palace. Archived from the original on 14 June 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ "Pungnap-toseong (Earthen Ramparts)". Seoul Metropolitan Government. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ "Sungnyemun to open to great fanfare after more than five years of renovation". The Korea Herald. 30 April 2013. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ^ "Status of Museum". Seoul Metropolitan Government. Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ "Seoul's best museums". CNN. 27 October 2011. Archived from the original on 16 September 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ^ "National Folk Museum of Korea". Korea Tourism Organization. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ "Namsangol Hanok Village". Korea Tourism Organization. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ "Bukchon Hanok Village". Korea Tourism Organization. Archived from the original on 15 September 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ Veale, Jennifer. "Seoul: 10 Things to Do". Time. Archived from the original on 27 September 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ "The War Memorial of Korea". Korea Tourism Organization. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ "Seodaemun Prison History Museum". Korea Tourism Organization. Archived from the original on 4 June 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ "ABU TV and Radio Song Festivals 2012". ESCKAZ.com. Archived from the original on 10 April 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ "ABU GA Seoul 2012". Asia-Pacific Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 3 March 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ "Ultra Korea – June 8, 9, 10 2018". Ultra Korea. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ^ "New York Times opens Asia news hub in Seoul". Korea JoongAng Daily. 11 May 2021.

- ^ "The Washington Post announces breaking-news reporters for Seoul hub". The Washington Post. 12 July 2021.

- ^ 2016 프로야구와 프로축구는 모두'서울의 봄' (in Korean). Medeaus Ilbo. 7 November 2016. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ "The subway's past and present". Korea.net. Archived from the original on 18 February 2023.

- ^ "Expanded Operation of Seoul Bike "Ddareungi"". Seoul Metropolitan Government. 18 March 2016. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019.

- ^ "Sister & Friendship Cities -". Official Website of the Seoul Metropolitan Government. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ "Exchange Cities of Seoul Metropolitan Council". Seoul Metropolitan Council. Archived from the original on 7 September 2022. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

Sources

- 서울 2천년사 [Seoul: A 2,000-Year History] (in Korean). Vol. 2. 서울지역의 선사문화. Seoul Historiography Institute. 20 December 2015. ISBN 9788994033839.

- 서울 2천년사 [Seoul: A 2,000-Year History] (in Korean). Vol. 3. 한성백제의 건국과 발전. Seoul Historiography Institute. 20 December 2015. ISBN 9788994033839.

External links

The dictionary definition of Seoul at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of Seoul at Wiktionary Media related to Seoul (category) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Seoul (category) at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Seoul at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Seoul at Wikiquote Seoul travel guide from Wikivoyage

Seoul travel guide from Wikivoyage

Official sites

- Official website (in English)

- Seoul Information & Communication Plaza website (in Korean)

Tourism and living information

- i Tour Seoul – The Official Seoul Tourism Guide Site